When you think of a generic drug, you picture a small pill that looks different but works just like the brand-name version. It’s simple chemistry - same molecules, same effects, cheaper price. But biosimilars are not like that. They’re not copies. They’re highly similar versions of complex biologic drugs made from living cells - and getting them right is one of the toughest engineering challenges in modern medicine.

Why Biosimilars Can’t Be Copied Like Pills

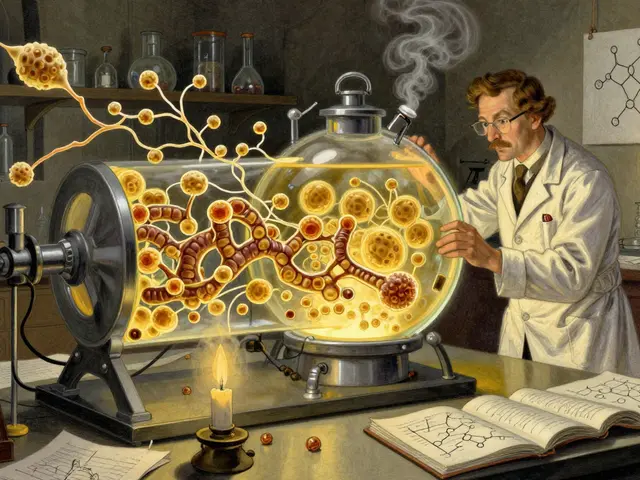

A generic aspirin is made by mixing chemicals in a reactor. The result is always the same molecule. But a biosimilar like adalimumab (Humira) or rituximab (Rituxan) is a protein - sometimes over 1,000 times bigger than a small-molecule drug. These proteins are grown inside living cells, usually Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, in giant bioreactors. The cells act like tiny factories, stitching together amino acids into a 3D structure that can change based on tiny shifts in temperature, pH, nutrients, or oxygen levels. This is why the saying in biopharma is: “The process defines the product.” You can’t just reverse-engineer the final molecule. You have to rebuild the entire system that makes it. And you don’t have the recipe. The originator company keeps its cell line, feeding strategy, purification steps, and storage conditions secret. So biosimilar makers are like chefs trying to recreate a Michelin-star dish without knowing the ingredients, stove settings, or cooking time.Glycosylation: The Silent Dealbreaker

One of the biggest hurdles is glycosylation - the addition of sugar chains to the protein. These sugars aren’t just decoration. They affect how long the drug lasts in your body, how strongly it binds to its target, and whether your immune system reacts to it. A slight change in glycosylation can turn a safe, effective drug into one that causes allergic reactions or clears too fast to work. But glycosylation is wildly sensitive. A 0.5°C shift in bioreactor temperature. A different batch of amino acids in the culture media. A change in how air is bubbled through the tank. All of these can alter the sugar profile. To match the reference product, manufacturers must measure dozens of glycan variants using advanced mass spectrometry. They then tweak their process - over hundreds of trials - until the glycosylation pattern falls within strict regulatory limits. Even then, each batch must be checked. There’s no room for error.Scale-Up: When the Lab Doesn’t Work in the Factory

Getting a biosimilar to work in a 10-liter lab bioreactor is one thing. Scaling it to 2,000 liters for commercial use is another. In small tanks, everything mixes evenly. In big ones, you get dead zones. Oxygen doesn’t reach all the cells. Temperature gradients form. Cells in one corner grow faster than those in another. This isn’t just a matter of making the tank bigger. It’s about redesigning how you stir, feed, and control conditions. A mixing speed that works in a 50-liter tank might shear cells in a 10,000-liter one. Too much oxygen kills cells. Too little slows protein production. Many smaller manufacturers can’t afford the expensive, custom-built equipment needed for large-scale production. They’re stuck trying to make complex drugs in outdated facilities. Some even have to build new production halls just to fit the bioreactors.

Cold Chain and Packaging: One Mistake, Millions Lost

Biosimilars don’t just need careful manufacturing. They need careful handling from the moment they’re made. These proteins are fragile. If they get too warm, freeze too fast, or are shaken during transport, they can clump, break down, or lose their shape. Once that happens, the drug is useless - and potentially dangerous. The cold chain - the temperature-controlled supply line from factory to hospital - must stay perfect. A single broken refrigerated truck, a mislabeled storage container, or a delayed shipment can destroy an entire batch. Some biosimilars cost over $100,000 per batch to produce. One packaging error can mean losing a million dollars overnight.Regulatory Maze: Proving Similarity Is a Full-Time Job

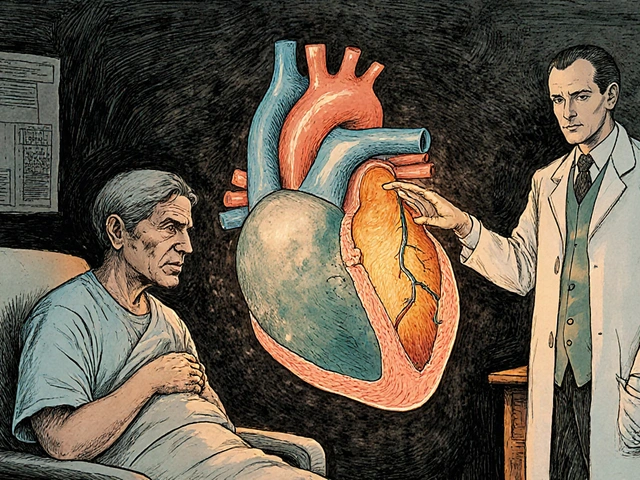

The FDA and EMA don’t just want a “close enough” answer. They demand proof - down to the last molecule. Manufacturers must run hundreds of analytical tests: structural analysis, functional assays, immunogenicity studies, and sometimes even clinical trials comparing side effects and efficacy. They need access to labs with $10 million worth of equipment - NMR spectrometers, high-resolution mass specs, flow cytometers - just to run the tests. And it’s not the same everywhere. The EU has stricter requirements than some Asian markets. The U.S. demands more clinical data than Canada. Each approval is a custom project. One country’s approval doesn’t guarantee another’s. This means biosimilar companies often need separate teams just to manage regulatory paperwork.

Technology Is Helping - But It’s Expensive

To fight these challenges, the industry is turning to new tools. Single-use bioreactors are replacing stainless steel tanks. They’re cheaper to clean, reduce contamination risk, and let manufacturers switch between products faster. Automated systems handle filling and packaging, cutting human error. Process Analytical Technology (PAT) lets engineers monitor critical parameters in real time - catching problems before they ruin a batch. Some companies are even using AI to predict how changes in temperature or nutrient levels will affect protein quality. Instead of trial-and-error, they simulate thousands of scenarios on a computer. But these technologies aren’t cheap. A single automated filling line can cost $50 million. Smaller players can’t compete. That’s why the biosimilar market is dominated by big players like Amgen, Samsung Bioepis, and Sandoz. New entrants need deep pockets and decades of bioprocessing experience.The Market Is Growing - But Only for the Few

The global biosimilars market was worth $7.9 billion in 2022 and is expected to hit $58.1 billion by 2030. That’s huge growth. But it’s not a free-for-all. The top five companies control over 70% of the market. Why? Because the barriers are so high. You need:- A team of 100+ scientists and engineers

- Millions in analytical equipment

- Years of regulatory experience

- Access to high-purity raw materials

- Capital to build or lease large-scale facilities

What’s Next? Complexity Is Only Getting Worse

The next wave of biosimilars won’t be simple monoclonal antibodies. They’ll be bispecific antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, and fusion proteins - molecules that do multiple jobs at once. These require even more steps: extra purification, refolding, chemical linking, and stability testing. Each new complexity adds another point where things can go wrong. A single mistake in conjugating a drug to an antibody can turn a life-saving treatment into a toxic one. The future belongs to manufacturers who can balance three things: scientific precision, regulatory compliance, and cost control. Only those who master all three will survive.For patients, this means biosimilars will keep lowering drug prices - but slowly. For manufacturers, it means the race isn’t just about who can make the drug. It’s about who can make it right, every time, without fail.

Why can’t biosimilars be made like regular generics?

Regular generics are made by chemically synthesizing identical small molecules. Biosimilars are large, complex proteins grown in living cells. Even tiny changes in the production process - like temperature or nutrient levels - can alter their structure and function. You can’t just copy the final molecule; you have to rebuild the entire biological system that makes it.

What is glycosylation and why does it matter for biosimilars?

Glycosylation is the attachment of sugar chains to protein molecules. These sugars affect how long the drug stays in the body, how well it binds to its target, and whether it triggers an immune response. Even small differences in glycosylation patterns between a biosimilar and its reference product can make the drug less effective or unsafe. Manufacturers must match these sugar structures exactly - which requires advanced lab equipment and hundreds of process trials.

Why is scaling up biosimilar production so difficult?

In small lab bioreactors, conditions like oxygen levels and mixing are easy to control. In large commercial tanks, these conditions become uneven. Cells in one part of the tank may grow slower or produce different protein variants than those in another. Scaling up requires completely re-engineering the process - adjusting stirring speed, aeration, and feeding strategies - to make sure the cells behave the same way at every scale.

How do regulatory agencies verify biosimilarity?

Regulators require extensive analytical testing to prove the biosimilar matches the reference product in structure, function, and purity. This includes mass spectrometry, chromatography, and cell-based assays. For some drugs, they also require clinical trials comparing safety and effectiveness. The goal is to show no clinically meaningful differences - not just similarity, but proven equivalence.

Are biosimilars cheaper than original biologics?

Yes, but not by much - and it takes years to get there. While generics can cost 80-90% less than brand-name drugs, biosimilars typically cost 15-35% less. That’s because manufacturing them is extremely expensive and complex. The high cost of equipment, testing, and regulatory compliance eats into savings. Over time, as more manufacturers enter the market and technology improves, prices are expected to drop further.

What’s the biggest barrier for new companies trying to make biosimilars?

The biggest barrier is access to both capital and expertise. Building a biosimilar facility requires $100 million or more in upfront investment. You need scientists who understand cell culture, analytical chemistry, and regulatory pathways - and you need them all working together. Most startups can’t afford this. That’s why only large, experienced biopharma companies dominate the market.

srishti Jain

So biosimilars are basically the opioid of pharma-expensive, fragile, and everyone pretends they’re just as good as the real thing.

Hayley Ash

Oh wow a whole essay on why it’s hard to copy a protein. Shocking. Next you’ll tell us breathing is complicated when you’re allergic to air.

kelly tracy

Let me guess-Big Pharma is crying because someone might finally undercut their $200k/year drug. Meanwhile, patients are still choosing between insulin and groceries. This isn’t science-it’s capitalism with a lab coat.

Shae Chapman

This is why I respect scientists so much. Imagine spending years trying to make a protein behave like its sibling while everyone else just wants it cheaper. 🫡

Colin L

It’s fascinating how we’ve managed to engineer life at a molecular level to the point where a 0.5-degree temperature fluctuation can turn a life-saving therapy into a potential immunological disaster, yet we still can’t figure out how to make public transit in New York reliable-there’s a cosmic irony here, isn’t there? We build machines that can replicate the complexity of human biology but can’t fix a broken subway signal without a three-week delay and three union meetings. It’s like we’ve outsourced our collective sense of order to CHO cells and forgotten how to maintain our own infrastructure.

Nadia Spira

The entire biosimilar paradigm is a regulatory theater designed to appease neoliberal cost-cutters while maintaining monopolistic rent extraction. You’re not replicating a drug-you’re performing a high-stakes analytical mimicry ritual sanctioned by agencies that are functionally captured by the originator firms. The glycosylation metrics? Just KPIs dressed up as science.

Henry Ward

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me a company spent $200M and 10 years to make a copy that’s 30% cheaper? That’s not innovation, that’s corporate masochism. The real biosimilar is the one that just buys the original and repackages it with a new label.

Cheyenne Sims

The assertion that biosimilars are ‘not copies’ is misleading. They are copies-just copies that require extraordinary precision due to the inherent complexity of biologics. Terminology matters. Precision in language reflects precision in science.

henry mateo

i just read this whole thing and wow. i had no idea how hard this was. my cousin takes a biosimilar and i always thought it was just a cheaper version. turns out its like trying to clone a snowflake while blindfolded. thanks for explaining.

Kunal Karakoti

If the process defines the product, then perhaps the real challenge isn’t manufacturing-it’s accepting that some things cannot be reduced to cost-efficiency. Life, at its core, resists optimization. The biosimilar is not just a drug. It is a testament to our hubris and humility in equal measure.

Joseph Corry

You speak of glycosylation as if it’s some mystical alchemical process, yet the entire enterprise is predicated on replicating what nature-through decades of evolution-has already optimized. We’re not engineers of biology; we’re desperate imitators clinging to patents like a drowning man to driftwood. The real innovation? Letting go.