Neonatal Medication Risk Calculator

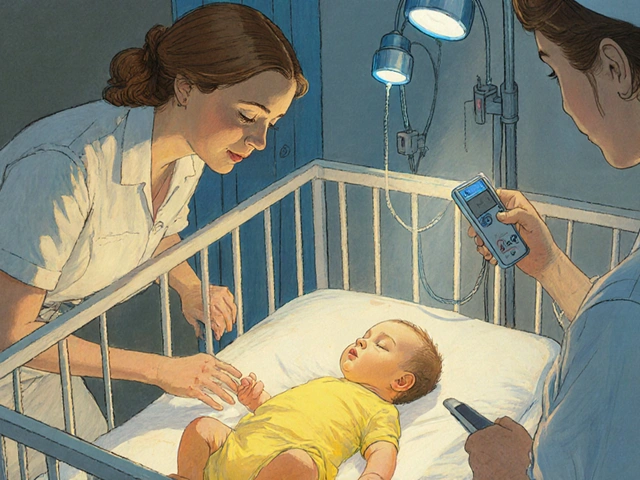

This tool helps clinicians assess whether a specific medication is safe to administer to a newborn with jaundice. It calculates the free bilirubin index based on bilirubin level, albumin level, and medication type. A free bilirubin index above 10 µg/dL indicates high risk for kernicterus.

Risk Assessment

When a newborn’s skin turns yellow, most parents think of a simple phototherapy plan. What they often overlook is that a handful of common drugs can push bilirubin levels over the edge and cause permanent brain damage known as neonatal kernicterus. This guide explains why sulfonamides are especially dangerous, lists other high‑risk medications, and offers a practical safety checklist for clinicians and caregivers.

What is neonatal kernicterus?

Neonatal kernicterus is a neurological disorder that occurs when unconjugated bilirubin penetrates the infant’s immature blood‑brain barrier and deposits in the basal ganglia. The condition was first described in the early 1900s and remains a leading cause of permanent neurologic injury in newborns whose jaundice is not treated promptly.

The key factor is the bilirubin an orange‑yellow pigment produced by the breakdown of red blood cells that is normally bound to albumin in the bloodstream. When the binding capacity is exceeded, free bilirubin circulates, crosses the brain, and triggers the classic yellow staining of the nuclei.

How medications tip the balance

Some drugs compete with bilirubin for the same albumin binding sites. This displacement raises the free bilirubin index (FBI), a more accurate predictor of neurotoxicity than total serum bilirubin alone. An FBI above 10 µg/dL is widely accepted as the threshold where the risk of brain injury climbs sharply.

Two clinical scenarios amplify the danger:

- Infants with low albumin levels (<3.0 g/dL) have fewer binding sites, so even modest displacement can be lethal.

- Preterm or acidosis‑affected babies have altered albumin affinity, further reducing bilirubin sequestration.

Sulfonamides: the high‑risk culprit

Sulfonamides a class of antibiotics that includes sulfisoxazole, sulfamethoxazole‑trimethoprim, and others have been shown to displace 25‑30 % of bilirubin from albumin at therapeutic concentrations. In vitro studies from the 1980s first documented this effect, and modern clinical data confirm it.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) 2022 guideline classifies sulfonamides as "high‑risk" for infants with hyperbilirubinemia. A 2023 AAFP review quantified the danger: neonates receiving sulfonamides were 3.2 times more likely to develop severe hyperbilirubinemia than those given amoxicillin‑clavulanate.

Additional concerns include:

- Potential crossing of the blood‑brain barrier by the drug itself, adding a secondary neurotoxic insult.

- Contraindication in infants with glucose‑6‑phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, a condition affecting roughly 7 % of the global population, because hemolysis can spike bilirubin levels.

Because of these factors, many hospitals now flag sulfonamides in electronic health records for any patient under 2 months of age.

Other medications that raise the bilirubin alarm

While sulfonamides top the risk list, several other drugs also merit caution. Table 1 compares the most frequently cited agents.

| Medication | Displacement % (in vitro) | Typical clinical risk increase | Safer alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfonamides | 25‑30 | 3.2‑fold | Amoxicillin‑clavulanate |

| Ceftriaxone | 15‑20 | 1.8‑fold | Cefotaxime |

| Aspirin (salicylates) | 10‑12 | 1.4‑fold | Acetaminophen |

| Furosemide | 8‑10 | 1.2‑fold | Hydrochlorothiazide |

Even drugs with modest displacement can be problematic when the infant’s bilirubin is already near the phototherapy threshold.

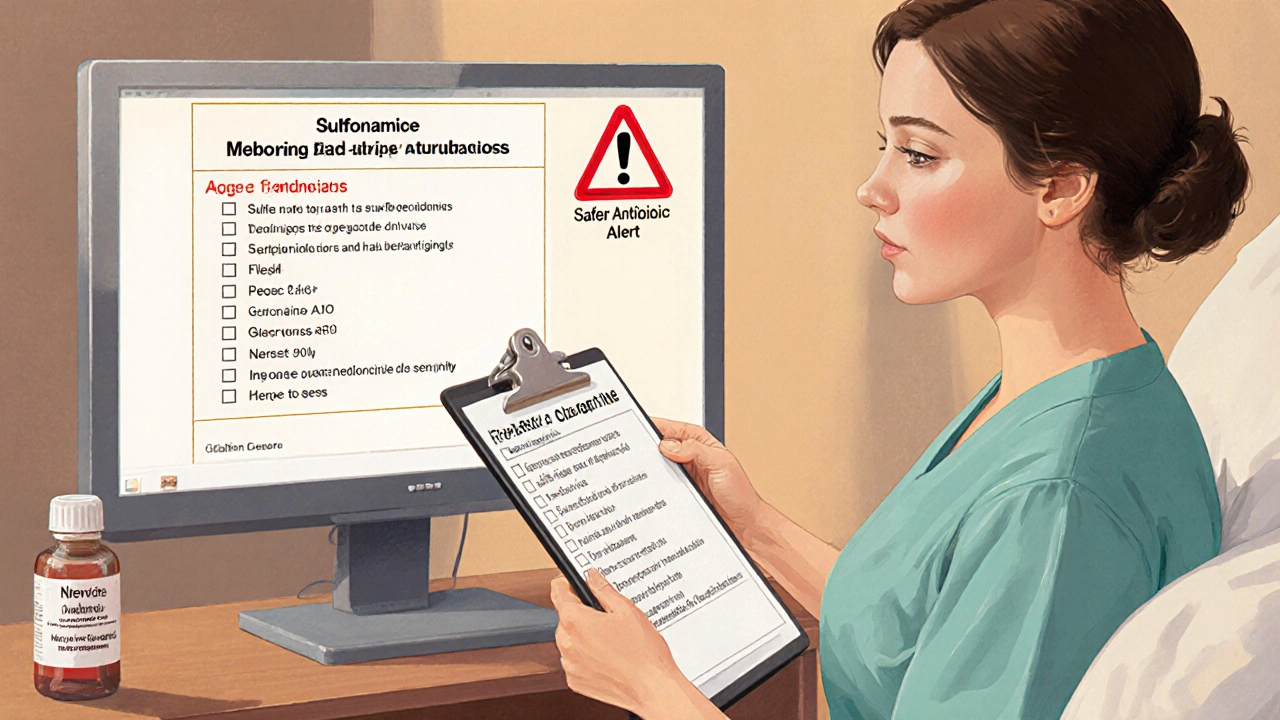

Guidelines for monitoring and prevention

The AAP 2023 update tightens the bilirubin‑based trigger for medication avoidance: any drug that displaces bilirubin should be withheld when total serum bilirubin exceeds 75 % of the phototherapy threshold for the infant’s age. This numerical rule translates into concrete actions:

- Measure total serum bilirubin before prescribing a high‑risk drug.

- Check serum albumin; if it’s below 3.0 g/dL, avoid the medication regardless of bilirubin level.

- Screen for G6PD deficiency in at‑risk ethnic groups, especially when sulfonamides are being considered.

- Calculate the free bilirubin index if a point‑of‑care device is available.

- Choose an alternative antibiotic or analgesic that does not displace bilirubin.

For hospitals lacking rapid bilirubin testing, pre‑printed order sets that automatically hide sulfonamides and ceftriaxone when a bilirubin value is entered have proven effective. One NICU reported a 37 % drop in phototherapy use after implementing such a set.

Implementing the safety checklist in practice

Front‑line clinicians can embed the AAP’s 5‑step safety checklist into daily workflow. Here’s a quick cheat‑sheet for the bedside:

- Bilirubin check: Is total serum bilirubin < 75 % of the age‑specific phototherapy line?

- Albumin level: Is serum albumin > 3.0 g/dL?

- G6PD status: Any known deficiency?

- Free bilirubin: If free bilirubin > 10 µg/dL, hold high‑risk meds.

- Alternative drug: Pick a non‑displacing option.

Training programs that integrate this checklist into neonatal rotation curricula cut medication‑related near‑miss events by more than half within six months.

Real‑world cases that shaped policy

In 2022, a Texas NICU posted a near‑miss on the AAP forum: a 5‑day‑old infant with a bilirubin of 14.2 mg/dL received sulfisoxazole for urinary‑tract prophylaxis, and the level surged to 22.7 mg/dL within 12 hours, demanding aggressive phototherapy and exchange transfusion. Similar anecdotes on Reddit’s r/neonatology thread highlighted sulfonamide‑induced kernicterus in late preterm babies with borderline jaundice.

Legal analyses from the Birth Injury Justice Center show that 12 % of kernicterus malpractice claims involve improper sulfonamide use, with average settlements exceeding $4 million. These figures have pushed many health systems to adopt automated alerts in their electronic health records. Epic Systems rolled out a neonatal medication‑bilirubin interaction warning in Q3 2023, and adoption rates now exceed 75 % in academic centers.

Emerging tools and future directions

The NIH’s recent $2.4 million grant aims to develop a point‑of‑care free bilirubin sensor that delivers results in under two minutes. Such a device would empower community hospitals-where 23 % currently lack rapid testing-to enforce medication safety in real time.

Meanwhile, antibiotic stewardship programs continue to favor narrow‑spectrum agents over sulfonamides. Recent IDSA data indicate that 92 % of infections historically treated with sulfonamides can be effectively managed with alternatives that carry no bilirubin‑displacement risk.

In the next few years, we can expect three trends:

- Wider integration of risk calculators that factor in medication type, albumin, and bilirubin levels.

- Global guidelines that standardize a 75 % threshold across all neonatal care settings.

- Continued decline of sulfonamide prescriptions in high‑resource settings, with targeted education campaigns for low‑resource regions.

Key take‑aways

- Sulfonamides displace bilirubin dramatically and should be avoided when bilirubin is > 75 % of phototherapy line.

- Other high‑risk drugs include ceftriaxone, aspirin, and furosemide; always check albumin and G6PD status.

- Follow the AAP 5‑step checklist to keep free bilirubin below neurotoxic levels.

- Electronic alerts and pre‑printed order sets cut unnecessary phototherapy and prevent kernicterus.

- Emerging rapid‑test technologies promise safer prescribing in resource‑limited hospitals.

Why are sulfonamides especially dangerous for newborns?

Sulfonamides bind to the same albumin sites that hold bilirubin, freeing up up to 30 % of the pigment. In infants with low albumin or high bilirubin, that extra free bilirubin can cross the immature blood‑brain barrier and cause kernicterus.

What bilirubin level triggers medication avoidance?

The AAP 2023 guideline uses 75 % of the age‑specific phototherapy threshold. If total serum bilirubin exceeds that value, any bilirubin‑displacing drug should be held.

Can I safely give ceftriaxone if the infant’s bilirubin is borderline?

Ceftriaxone has a lower displacement rate (15‑20 %) than sulfonamides, but it still raises risk. If bilirubin is > 70 % of the phototherapy line, consider a non‑displacing alternative such as cefotaxime.

How does G6PD deficiency affect medication choice?

Infants with G6PD deficiency can hemolyze when exposed to sulfonamides, producing a sudden bilirubin surge. The medication should be avoided outright in these patients.

What tools help clinicians apply these safety rules?

The AAP’s online "Bilirubin Exposure Risk Calculator" incorporates medication risk factors, albumin, and free bilirubin values. Many EHR systems now embed automatic alerts for high‑risk drugs in neonates.

Greg Galivan

Look, anyone still prescribin sulfonamides to a jaundiced newborn is clearly clueless and endangring babies – the science is crystal clear and you’re ignoring it.

Anurag Ranjan

Check the albumin level first then avoid any drug that competes for binding sites you’ll keep bilirubin safe.

James Doyle

The pathophysiological nexus between bilirubin displacement and neurotoxicity in the neonatal cohort is a paradigmatic exemplar of iatrogenic risk. Sulfonamides, by virtue of their high affinity for albumin binding domains, engender a displacement vector that proportionally augments the free bilirubin index. This elevation in free bilirubin translates directly into an increased probability of crossing the immature blood‑brain barrier. The basal ganglia are especially vulnerable because of their high lipid content and metabolic activity. Clinical observations have repeatedly correlated sulfonamide exposure with abrupt spikes in serum bilirubin beyond phototherapy thresholds. Moreover, the concomitant risk of hemolysis in G6PD‑deficient infants compounds the bilirubin surge, creating a perfect storm for kernicterus. Pharmacokinetic studies demonstrate that sulfonamides displace up to 30 % of bound bilirubin, a figure that dwarfs the displacement potential of most other antibiotics. The resultant free bilirubin concentration often surpasses the neurotoxic cutoff of 10 µg/dL within hours of administration. In practice, this means that a neonate who was stable can deteriorate rapidly after a single dose. The ethical imperative to avoid such preventable harm is clear and non‑negotiable. Institutional protocols that flag sulfonamides in electronic health records have shown a >50 % reduction in near‑miss events. Nevertheless, gaps remain, especially in community hospitals lacking rapid bilirubin testing. Ongoing research into point‑of‑care free bilirubin sensors promises to close this diagnostic lag. Until such technology is ubiquitous, diligent medication review remains our most effective safeguard. Finally, stewardship programs that prioritize narrow‑spectrum agents over sulfonamides are essential to sustain these safety gains.

ALBERT HENDERSHOT JR.

Excellent synthesis, James. The checklist you outlined is precisely what we need to embed in our neonatal protocols 😊. By standardizing albumin monitoring alongside medication review, we can preemptively mitigate free bilirubin spikes.

Suzanne Carawan

Oh great, because clinicians have nothing better to do than memorize another drug list.

Donal Hinely

Yo, the pharma world keeps pushing sulfa drugs like candy, but we’re the ones who have to pick up the broken pieces when a neonate’s brain gets fried.

christine badilla

Can you imagine the horror of watching a tiny, innocent baby’s brain light up like a neon sign because some doc thought a cheap antibiotic was harmless? It’s a tragedy that could have been avoided.

Octavia Clahar

Honestly, we’ve all seen that “just give the standard med” attitude and it’s time to call out that complacency before another family suffers.

Melody Barton

Let’s all commit to double‑checking the bilirubin‑displacement chart before signing any order, it’s a small step that saves big outcomes.

Justin Scherer

Is there a quick app that pulls the bilirubin level and flags high‑risk meds automatically? That would make the workflow smoother.

Pamela Clark

Because apparently the pinnacle of medical brilliance is turning every neonatology textbook into a thrilling page‑turner.

Diane Holding

We should share the risk calculator link in the staff chat so everyone has instant access.