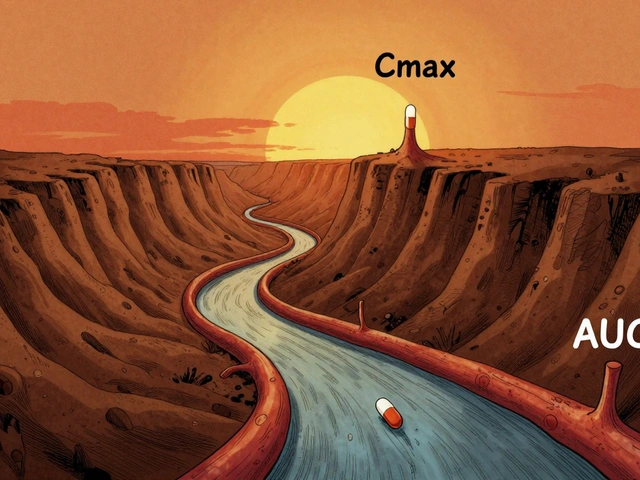

When a generic drug hits the market, how do we know it works just like the brand-name version? It’s not about looking at the pill color or checking the label. It’s about two numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just technical terms for pharmacologists-they’re the gatekeepers of whether a generic drug is safe and effective for you.

What Cmax and AUC Actually Measure

Cmax stands for maximum concentration. It tells you the highest level of drug in your bloodstream after you take it. Think of it like the peak of a rollercoaster-the highest point before it drops. If a drug needs to hit a certain concentration quickly to relieve pain or stop a seizure, Cmax is what matters most.

AUC, or area under the curve, is the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time. Imagine drawing a graph of drug levels in your blood from the moment you swallow the pill until it’s all gone. AUC is the space under that line. It’s not about how high the peak is-it’s about how long the drug stays active in your system.

For example, if you take a painkiller, a high Cmax means you feel relief fast. But if you’re taking a blood thinner like warfarin, it’s the AUC that keeps you safe-too little exposure and you risk a clot; too much and you bleed. Both numbers are critical, but for different reasons.

Why Both Numbers Are Required

Regulators don’t just look at one. They require both Cmax and AUC to pass the same test. Why? Because a drug could have the same total exposure (AUC) but be absorbed too slowly or too fast. That changes how it works in your body.

Take an immediate-release antibiotic. If the generic version releases the drug too slowly, Cmax might be too low to kill bacteria at the start. Even if the total AUC is fine, you could end up with a treatment that fails. On the flip side, if Cmax is too high, you might get side effects-like dizziness or nausea-before the drug settles into a steady state.

The rule is simple: both must meet the standard. One failure means the whole product fails. There’s no compromise. This isn’t just bureaucracy-it’s science. A 2021 analysis of 500 bioequivalence studies found that 78% of generics passed the Cmax test, while 82% passed AUC. That small gap shows why both are needed. Cmax is often the trickier one to nail.

The 80%-125% Rule: How Much Difference Is Allowed?

Here’s the magic number: 80% to 125%. That’s the range regulators accept for both Cmax and AUC. If the generic’s Cmax is 95% of the brand’s, you’re good. If it’s 78%? It’s rejected. Same with AUC.

This range isn’t random. It comes from decades of data and statistical modeling. On a logarithmic scale, 80% and 125% are symmetrical around 100%-meaning a 20% drop is treated the same as a 25% rise. That’s because drug levels in blood don’t follow a straight line; they follow a curve that’s skewed. Logarithmic transformation fixes that.

Why not 90%-110%? Because for most drugs, a 20% difference in exposure doesn’t change how well it works or how safe it is. A 2019 review of 42 studies in JAMA Internal Medicine found no meaningful difference in outcomes between generics and brand-name drugs that met this standard.

But there are exceptions. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, lithium, or levothyroxine-even a 10% change can be dangerous. That’s why the EMA now recommends tighter limits (90%-111%) for these drugs. The FDA hasn’t adopted this universally, but it’s under review.

How Bioequivalence Studies Work

Before a generic drug is approved, it goes through a clinical study-usually with 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. Each person takes both the brand and the generic, in random order, with a washout period in between. Blood is drawn 12 to 18 times over 3 to 5 days to map out how the drug moves through the body.

The most critical part? Sampling during the first 1 to 3 hours. That’s when Cmax happens. If you miss the peak because blood draws are too far apart, your Cmax number is wrong. And if Cmax is wrong, the whole study fails. Industry data shows this is the #1 reason bioequivalence studies don’t pass.

Modern labs use LC-MS/MS machines that can detect drug levels as low as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter. That’s one-billionth of a gram. Without this precision, we couldn’t measure low-dose drugs like levothyroxine or hormonal treatments accurately.

After the data is collected, it’s analyzed using specialized software like Phoenix WinNonlin. The values are log-transformed, ratios are calculated, and 90% confidence intervals are built. Only if both AUC and Cmax fall within 80%-125% does the drug get approved.

What Happens When the Numbers Don’t Match?

Not every generic passes. When a product fails, it’s not because the company is cutting corners-it’s often because the formulation is slightly different. Maybe the binder changes how fast the tablet dissolves. Or the particle size affects absorption. These tiny differences matter.

Some drugs are just harder to copy. Highly variable drugs-where one person’s Cmax might be 50% higher than another’s even with the same brand-pose a unique challenge. The EMA allows something called “scaled average bioequivalence” for these cases, which adjusts the acceptance range based on how much the drug varies between people. The FDA doesn’t use this method for all drugs, but it’s an option for certain ones.

Still, over 90% of generics pass on the first try. That’s because manufacturers spend years optimizing their formulas to match the original. They don’t just copy the active ingredient-they reverse-engineer the entire delivery system.

Why This Matters for You

You might think, “If it’s generic, it’s cheaper-so it must be less effective.” That’s a myth. The science behind Cmax and AUC is designed to prevent exactly that.

When you take a generic blood pressure pill, you’re not gambling. The same strict standards apply as for the brand. That’s why the FDA approves over 1,200 generic drugs every year-and why millions of people rely on them safely.

For patients on chronic meds, consistency matters. If your generic switches from one manufacturer to another, you might worry. But if both meet the 80%-125% rule, your body won’t notice the difference. That’s the power of pharmacokinetics.

And it’s not just about cost. In countries without universal healthcare, generics make life-saving drugs accessible. Without Cmax and AUC as the gold standard, we’d have no way to ensure those drugs work.

The Future: Will Cmax and AUC Stay the Gold Standard?

Some scientists are asking if we need more than just two numbers. For complex drugs-like extended-release pills that release medicine in waves-AUC and Cmax might not tell the whole story. The FDA is exploring partial AUC measurements for these cases, looking at exposure during specific time windows.

Computer modeling is also getting better. Instead of testing 30 people, maybe we can simulate thousands of virtual patients. But even then, Cmax and AUC remain the baseline. As Dr. Robert Lionberger of the FDA said at a 2022 conference: “They’ve been validated for over 30 years. Until something better comes along, they’re staying.”

And for now, that’s good news. Because when you pick up a generic bottle, you want to know that the science behind it is solid. Cmax and AUC are that guarantee.

What does Cmax mean in bioequivalence?

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration-the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after taking it. It tells you how quickly the drug is absorbed and is especially important for drugs where timing affects effectiveness or side effects, like painkillers or seizure medications.

What is AUC in bioequivalence?

AUC, or area under the curve, measures total drug exposure over time. It’s calculated by plotting drug concentration in the blood against time and measuring the space under that curve. AUC tells you how much of the drug your body has absorbed overall, which is critical for drugs that work best with steady, sustained levels.

Why are both Cmax and AUC required for bioequivalence?

Because they measure different things. AUC shows total exposure, while Cmax shows how fast the drug enters the system. A drug could have the same total exposure as the brand but be absorbed too slowly or too quickly, leading to ineffective treatment or side effects. Both must pass the same 80%-125% range to ensure safety and effectiveness.

What is the 80%-125% rule in bioequivalence?

The 80%-125% rule means the ratio of the generic drug’s Cmax or AUC compared to the brand-name drug must fall between 80% and 125%. This range was established based on decades of clinical data showing that differences within this range are not clinically meaningful for most drugs. It’s applied using logarithmic transformation to account for how drug concentrations are distributed in the body.

Are there drugs that need tighter bioequivalence limits?

Yes. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, lithium, levothyroxine, and some anti-seizure medications-can be dangerous if exposure varies even slightly. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommends tighter limits of 90%-111% for these drugs. The FDA is considering similar changes but hasn’t made them universal yet.

Do bioequivalence studies always use healthy volunteers?

Most do-typically 24 to 36 healthy adults. This is because their bodies respond predictably, making it easier to isolate differences caused by the drug formulation. Testing in patients with the disease could introduce too many variables, like organ function or other medications. However, for some drugs (like cancer treatments), studies may be done in patients under strict conditions.

What happens if a generic drug fails bioequivalence testing?

The manufacturer must revise the formulation and resubmit for testing. This could mean changing the tablet’s binder, coating, particle size, or manufacturing process. Many companies go through multiple rounds before passing. If they can’t make it work, the generic drug won’t be approved for sale.

Can I trust a generic drug that passed bioequivalence testing?

Yes. Over 1,200 generic drugs are approved each year by the FDA, all meeting the same strict standards as brand-name drugs. A 2019 analysis of 42 studies found no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness between generics and brands that passed bioequivalence tests. The science behind Cmax and AUC has been validated for over 30 years.

kelly mckeown

i just took my generic blood pressure med this morning and honestly? i never thought about how they make sure it works the same. this post made me feel way less anxious about switching brands. thanks for explaining it so clearly.

Tom Costello

Love how this breaks down the science without dumbing it down. The 80%-125% rule always seemed arbitrary until someone explained the log transformation. That’s actually elegant math.

Susan Haboustak

So you're telling me the FDA lets drugs with up to 25% higher concentration into the market? That’s reckless. People die from overdoses. This system is broken.

Siddharth Notani

Excellent explanation. 🙏 In India, generics save lives daily. The Cmax-AUC standard ensures that even the poorest patient receives safe medicine. Science > profit.

Akash Sharma

Actually, I’ve been reading up on this for my pharmacology thesis, and I think there’s something missing here. The 80%-125% range is fine for most drugs, but what about drugs with high inter-individual variability? Like phenytoin or cyclosporine? The EMA’s scaled bioequivalence approach is way more nuanced-it accounts for within-subject variability and adjusts the limits dynamically. The FDA’s reluctance to adopt this broadly is frustrating because it means some patients get generics that are statistically equivalent but clinically inconsistent. I’ve seen case reports where switching generics caused seizures in epileptic patients even though both passed bioequivalence. The issue isn’t the method-it’s the rigid application. Maybe we need tiered standards based on therapeutic index and variability profiles instead of a one-size-fits-all rule.

Justin Hampton

Of course the FDA approves these. Big Pharma owns them. You think they’d let a cheap generic compete if it wasn’t rigged? Cmax? AUC? Just buzzwords to make you feel safe while your insurance company profits.

Pooja Surnar

Ugh. Why do people trust this crap? My cousin took a generic levothyroxine and went into thyroid storm. The FDA is lazy. They should ban all generics. Real medicine costs money.

Sandridge Nelia

This is such a clear breakdown! I’m a nurse and I use this info to reassure patients all the time. The 80-125% rule is a lifesaver (literally). 💙

Mark Gallagher

Why are we letting foreign manufacturers make our medicine? This is a national security issue. Cmax and AUC don’t matter if the pills are made in a factory with no oversight. We need American-made generics. Period.

Erik van Hees

Wait, hold on. You’re saying the FDA doesn’t even test the drug in actual patients? Just healthy volunteers? That’s insane. What if the drug behaves totally differently in someone with liver disease or diabetes? You’re telling me a 22-year-old college kid’s blood levels are a proxy for my 68-year-old dad with congestive heart failure? That’s not science-that’s gambling. And you wonder why people don’t trust generics?

Cristy Magdalena

Everyone’s so quick to defend this system… but what about the people who actually feel different on generics? My migraines got worse. My anxiety spiked. I changed back to brand and it was like night and day. They call it ‘no meaningful difference’-but my body knows better. Who’s listening to us?

Adrianna Alfano

Thank you for this. I’ve been on levothyroxine for 15 years and switched generics three times. Once I felt like I was floating. Another time, I couldn’t get out of bed. I didn’t know it was the Cmax until I read this. Now I ask my pharmacist for the exact manufacturer every time. It’s not paranoia-it’s survival.

Casey Lyn Keller

So you’re saying the government lets companies fake the data? I mean, how do we even know they’re not just making up the blood draw times? I’ve seen documentaries. They don’t even test all the samples. This whole thing is a scam.

Jessica Ainscough

I’ve been a pharmacist for 18 years and I can tell you-99% of generics are perfect. The ones that cause issues? Usually from small, unknown labs. Stick with the big names. And if you’re worried? Ask for the manufacturer name. Most pharmacists will tell you. You’re not being paranoid-you’re being smart.