If you’ve ever looked in the mirror and noticed a pink, fleshy wedge growing from the white of your eye toward the pupil, you’re not alone. This isn’t a rare oddity-it’s pterygium, commonly called "Surfer’s Eye." And if you live in a sunny place like Melbourne, Australia, or anywhere near the equator, your risk is higher than you might think. About 12% of Australian men over 60 have it. For outdoor workers, surfers, farmers, and even daily commuters without proper eye protection, the numbers climb even higher. The good news? You can stop it from getting worse. The better news? If it does grow, surgery can fix it-with smart techniques that work.

What Exactly Is Pterygium?

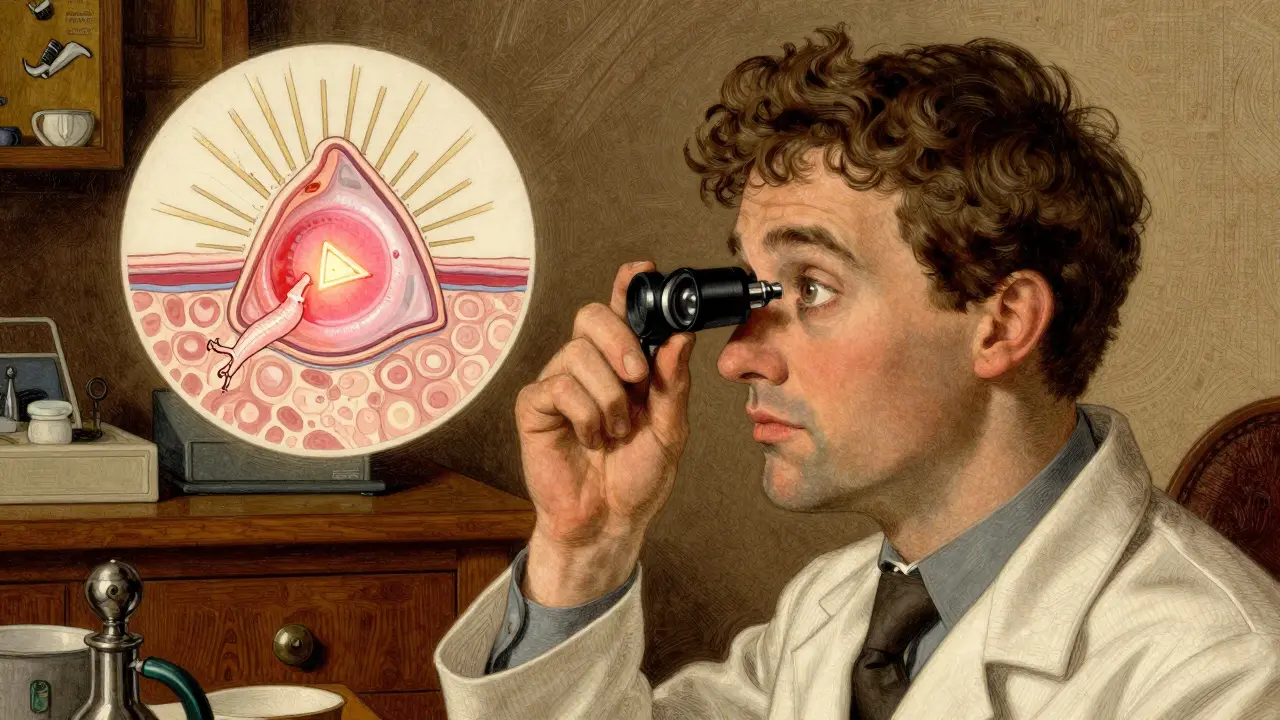

Pterygium isn’t a tumor. It’s not cancer. It’s a harmless, though annoying, growth of the conjunctiva-the clear, thin tissue that covers the white part of your eye. It starts near the nose, stretches across the sclera (the white), and creeps onto the cornea (the clear front surface). That’s what makes it different from pinguecula, a similar bump that stays on the white part and never crosses into the cornea. When it crosses over, it’s officially a pterygium.

It looks like a thin, triangular wing-hence the name, from the Greek word "pterygion," meaning "little wing." It’s often pink or red, with visible tiny blood vessels. At first, it might just be a slight discoloration. But over time, it can thicken, become opaque, and even distort your vision. If it grows far enough, it can cause astigmatism, making everything look blurry. Some people feel grittiness, dryness, or constant irritation, like sand is stuck in their eye.

Why Does Sun Exposure Make It Grow?

UV radiation is the main driver. Not just a little sun-it’s cumulative exposure. Think of it like sunburn on your skin, but on your eye. Every day you’re outside without protection, your eyes soak up UV rays. Over years, this damages the conjunctival tissue, triggering abnormal cell growth.

Studies show people living within 30 degrees of the equator have a 2.3 times higher risk. In Australia, where UV levels regularly hit extreme levels, the prevalence jumps to 23% among adults over 40. Research from the University of Melbourne found that those with over 15,000 joules of UV exposure per square meter-roughly 3,000 hours of unprotected outdoor time-had a 78% increased chance of developing pterygium.

It’s not just beach days. It’s driving with the window down, gardening, fishing, hiking, or even working outside during lunch. Snow, water, and sand reflect UV rays, doubling your exposure. And here’s the kicker: many people think sunglasses are just for bright days. But UV rays are present even on cloudy days. If your sunglasses don’t block 99-100% of UVA and UVB, you’re still at risk.

How Do Doctors Diagnose It?

No blood tests. No scans. It’s all in the eye. An ophthalmologist uses a slit-lamp-a bright, magnified light-to examine your eye. At 10 to 40 times magnification, they can see exactly how far the growth has traveled onto the cornea, how thick it is, and whether blood vessels are actively feeding it. That’s critical because not all pterygia need treatment. Some stay small for decades without causing problems.

They’ll also check for signs of astigmatism, which happens when the pterygium pulls on the cornea and changes its shape. If your vision is blurry and you’re not nearsighted, that could be why.

Most cases are diagnosed during routine eye exams. If you’ve been told you have a "pinguecula" before and now it’s growing toward your pupil, that’s a red flag. Don’t wait for symptoms to worsen. Early detection means easier management.

Can You Stop It From Growing?

Yes. And it starts with protection.

- Wear UV-blocking sunglasses every day, even when it’s overcast. Look for labels that say "100% UV protection" or "UV400." ANSI Z80.3-2020 standards ensure they block both UVA and UVB.

- Pair them with a wide-brimmed hat. This cuts UV exposure to your eyes by up to 50%.

- Use lubricating eye drops if your eyes feel dry or gritty. Preservative-free drops are best for long-term use.

- Avoid staring directly at the sun. Even brief exposure adds up.

One Reddit user, "OutdoorPhotog," shared that after 10 years of wearing UV-blocking sunglasses daily, his pterygium stopped growing entirely. His doctor confirmed it during two annual check-ups. That’s the power of prevention.

There’s no cream, pill, or eye drop that shrinks an existing pterygium. But if it’s mild and not affecting vision, conservative care-sun protection and artificial tears-is often all you need.

When Does Surgery Become Necessary?

Surgery isn’t always needed. But if you’re experiencing:

- Blurry or distorted vision

- Chronic irritation that won’t go away

- Difficulty wearing contact lenses

- Significant cosmetic concern

Then it’s time to talk to an eye surgeon. The goal isn’t just to look better-it’s to preserve your vision. A pterygium that covers the pupil can permanently alter how light enters your eye.

Traditionally, surgeons would just scrape it off. But that led to recurrence in 30-40% of cases. Today, the standard is more advanced.

What Are the Best Surgical Options?

There are three main techniques, each with pros and cons:

| Technique | Recurrence Rate | Recovery Time | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Excision | 30-40% | 2-4 weeks | Quick, low cost | High chance of coming back |

| Conjunctival Autograft | 8.7% | 3-6 weeks | Lowest recurrence, durable | More complex, longer healing |

| Mitomycin C + Excision | 5-10% | 2-4 weeks | Effective, shorter recovery | Risk of corneal thinning, needs careful use |

The most popular method today is conjunctival autograft. The surgeon removes the pterygium and replaces it with a tiny piece of healthy conjunctiva taken from under your eyelid. It’s like a skin graft, but for your eye. This technique reduces recurrence to under 10%.

Another option is using mitomycin C, a chemotherapy drug applied briefly during surgery to kill off abnormal cells. It’s very effective but carries a small risk of corneal thinning if overused. That’s why it’s usually reserved for more aggressive cases or those that have returned before.

As of June 2023, the European Society of Cataract & Refractive Surgeons now recommends amniotic membrane transplantation for recurrent pterygium. It’s a biological patch from donated placental tissue that promotes healing and reduces inflammation. Early results show a 92% success rate in preventing regrowth.

Surgery itself takes about 30-45 minutes. It’s done under local anesthesia-you’re awake but feel no pain. Most people go home the same day.

What’s Recovery Really Like?

Don’t expect instant relief. The first two weeks are the toughest.

- Your eye will be red, swollen, and sensitive to light. That’s normal.

- You’ll need steroid and antibiotic eye drops for 4-6 weeks. Skipping doses increases the risk of recurrence.

- Some patients report discomfort like burning or a foreign body sensation for up to three weeks.

- Most people return to desk work in 3-5 days. Avoid swimming, dusty environments, and heavy lifting for at least two weeks.

One patient on RealSelf.com said: "The surgery took 35 minutes, but the steroid drops regimen for 6 weeks was more challenging than expected." That’s common. The drops are crucial-but they’re also a hassle.

Positive outcomes? 87% of patients report major relief from irritation. 65% notice improved vision right after healing. And 78% say recovery was quicker than they expected.

What About Recurrence?

It’s the biggest worry. About 1 in 3 people see the pterygium grow back if no advanced technique is used. Even with an autograft, 8-10% may experience regrowth. That’s why follow-up care matters.

If it comes back, don’t panic. Repeat surgery is possible, but each recurrence makes the next one harder to treat. That’s why the first surgery should be done right-with an autograft or mitomycin C.

Keep wearing your sunglasses. Even after surgery, UV exposure is the #1 reason it returns.

What’s New in Treatment?

The field is evolving fast. In March 2023, the FDA approved OcuGel Plus, a preservative-free lubricant designed specifically for post-surgery patients. Clinical trials showed it relieved dryness and discomfort 32% better than standard artificial tears.

Looking ahead, researchers are testing topical rapamycin-a drug used in organ transplants-to block the cells that cause pterygium to grow. Early Phase II trials show a 67% drop in recurrence at 12 months. That could mean fewer surgeries in the future.

By 2027, 78% of ophthalmologists expect to use laser-assisted removal as a standard. It’s less invasive, reduces bleeding, and may speed up healing.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Men are diagnosed more often than women-about 3 to 2. Why? Likely because more men work outdoors in high-risk jobs: construction, farming, fishing, landscaping. The International Labour Organization points to this occupational gap.

Age matters too. Most cases appear after 40, but with climate change and ozone depletion, younger people are showing up with early signs. In Australia, the average age of diagnosis has dropped by 8 years over the last decade.

Geography is key. If you live within 30 degrees of the equator-think Florida, Brazil, Southeast Asia, or Northern Australia-you’re in the high-risk zone. Even if you don’t surf, your daily life exposes you to enough UV to trigger growth.

What Should You Do Next?

Step 1: If you have any signs of a growth on your eye, see an ophthalmologist-not just your optometrist. They have the tools and training to assess progression.

Step 2: If it’s small and not bothering you, start wearing UV-blocking sunglasses every day. No exceptions. Add a hat. Use lubricating drops if needed.

Step 3: If it’s growing or affecting vision, schedule a consultation with a corneal specialist. Ask about autograft or mitomycin C. Don’t settle for simple removal.

Step 4: Keep track. Take photos of your eye every 6 months with your phone. Compare them at your check-ups. Small changes matter.

Pterygium isn’t life-threatening. But it can steal your clear vision-and it’s entirely preventable. The sun isn’t going away. But your protection can be.

wendy parrales fong

Had no idea this was so common. I’ve been wearing sunglasses since I was 12 because my grandma always said, "Don’t let the sun eat your eyes." Turns out she was right.

Now I just hope my kids don’t ignore this like I did in my 20s.

Jeanette Jeffrey

Oh please. You think sunglasses stop it? My cousin worked on a cattle station in Queensland for 30 years. Wore sunglasses, a hat, even a face mask. Got pterygium at 42. UV isn’t the only culprit-it’s genetics and pure dumb luck. Stop pretending this is just about sunscreen for your eyeballs.

Shreyash Gupta

Bro… I live in Delhi. No UV protection. No sunglasses. Still no pterygium. 🤷♂️

Maybe it’s just rich people’s problem? Or maybe your data’s biased? 😏

Dan Alatepe

Y’all actin’ like this is some new horror movie. My granddaddy had one so big it looked like a tiny sail on his eyeball-still drove his tractor till he was 82. Surgery? Nah. He just blinked harder. 😅

Now I wear shades because I’m vain, not because I’m scared of my own cornea.

Angela Spagnolo

I’ve had a pinguecula since I was 30… and now it’s… slightly… bigger? I’m… terrified… but… I… keep… forgetting… to… wear… my… sunglasses… because… they… slip… off… my… nose… and… I… feel… ridiculous… in… them… 😅

Sarah Holmes

This is the kind of pseudo-medical fluff that makes people panic over minor cosmetic issues. You’re not going blind from a pink patch. You’re being sold fear by a $300 eye clinic. If you’re not in pain, don’t touch it. Let nature take its course. And stop promoting expensive surgeries as the only solution.

Michael Bond

Wear shades. Use drops. Get checked. Done.

Matthew Ingersoll

Back in Nigeria, we called this "sun sickness." No fancy terms. Just sun. No doctors. Just shade. My uncle worked under a palm tree for 40 years-never had one. Maybe it’s not just UV. Maybe it’s diet, or water, or how much you sweat. We never thought about it. We just lived.

carissa projo

Hey, if you’re reading this and you’ve been ignoring that little pink thing on your eye… I see you. I’ve been there too. But please-don’t wait until it’s blocking your vision. That moment when you realize you can’t see the road clearly while driving? It’s not worth it.

Wear the damn sunglasses. Even if you look like a spy. Even if your friends tease you. Your future self will thank you. And if you’ve already had surgery? You’re a warrior. I’m proud of you.

Also, try preservative-free drops. They’re a game-changer. I swear.

josue robert figueroa salazar

Surgery? Nah. I just stopped going outside. Works better than any graft.

david jackson

Okay, let’s get real for a second. The real issue here isn’t just the pterygium-it’s the entire medical-industrial complex turning a benign, slow-growing eye condition into a crisis that requires expensive, invasive procedures. I’ve read the studies. The recurrence rate with autografts is 8.7%? That’s not bad. But what’s the cost? What’s the psychological toll? What’s the emotional burden of being told, "You need surgery" when you’re just trying to enjoy your morning coffee outside?

And don’t even get me started on mitomycin C. A chemotherapy drug in your eye? That’s not treatment-that’s a gamble. Who’s monitoring the long-term corneal thinning? Who’s tracking the patients who develop corneal ulcers months later because they didn’t know how to properly use steroid drops?

Meanwhile, the real solution-sun protection-is free. It’s accessible. It’s been known for decades. But it doesn’t make for a viral TikTok video. It doesn’t get you a $5,000 surgical fee. So instead, we get 12-part YouTube series with slow-motion clips of surgeons peeling tissue off eyeballs while ominous music plays.

And yes, I know the author mentioned prevention. But the whole tone of this post screams: "You’re one bad day away from losing your vision-get surgery now." That’s not medicine. That’s marketing dressed in white coats.

So I’m not saying don’t protect your eyes. I’m saying don’t let fear drive your decisions. Go to your ophthalmologist. Get a second opinion. Ask about the recurrence rates. Ask about alternatives. Ask what happens if you do nothing. And then-please-make your choice based on science, not salesmanship.