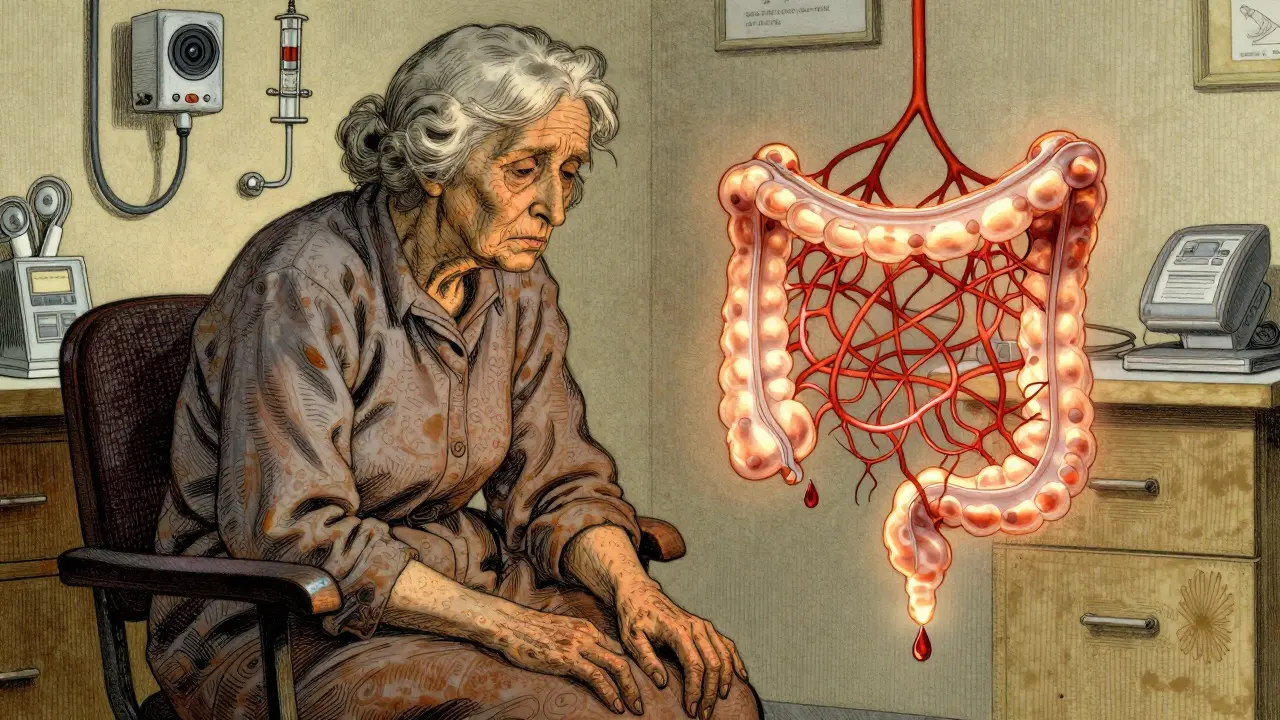

When you see bright red blood in your stool, it’s natural to panic. But not all lower GI bleeding is the same. Two of the most common causes-diverticula and angiodysplasia-look very different, behave differently, and need very different approaches. Both are more common as you get older, especially after 60, and both can lead to serious complications if not properly diagnosed. The good news? Most cases stop on their own. The challenge? Knowing which one you’re dealing with, because treatment depends entirely on the cause.

What Exactly Is Lower GI Bleeding?

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding means blood coming from somewhere in your colon, rectum, or anus-anything past the ligament of Treitz, which is about halfway down your small intestine. It usually shows up as hematochezia: bright red or maroon blood mixed with stool or passed alone. Sometimes it’s just a streak on the toilet paper. Other times, it’s a full-blown gush that turns the toilet water red. It’s not the same as melena-that black, tarry stool that usually means bleeding higher up, like in your stomach or duodenum. But if upper GI bleeding is slow, blood can take days to pass, and it might look like lower GI bleeding. That’s why doctors don’t just guess-they test. About 1 in 5 cases of all GI bleeding come from the lower tract. It’s rare under age 40, but after 60, your risk goes up sharply. Men are slightly more affected than women, and people with heart disease, kidney failure, or on blood thinners are at higher risk.Diverticula: The Silent Bleeder

Diverticula are small pouches that bulge out from the wall of your colon. They’re super common-nearly half of people over 60 have them. Most never cause problems. But in about 1 in 4 of those with diverticula, one can start bleeding. This isn’t diverticulitis (which is infection and inflammation). This is pure, painless bleeding. You wake up one morning, go to the bathroom, and see a lot of blood. No cramps. No fever. No nausea. Just blood. It can be massive-enough to cause dizziness or fainting. Why does it happen? The blood vessels that feed the colon run close to the surface where diverticula form. Over time, these vessels get stretched and thin. A small tear, even from normal bowel movement pressure, can cause them to rupture. The bleeding often stops on its own because the colon contracts and compresses the vessel. Studies show diverticula cause 30% to 50% of all hospitalizations for lower GI bleeding. In one large study of over 12,000 patients, 30-day mortality was 10% to 22%, but that’s mostly because of other health problems-not the bleeding itself.Angiodysplasia: The Slow Leak

Angiodysplasia-also called vascular ectasia or AVM-is a tangle of abnormal blood vessels in the colon lining. They’re most often found on the right side of the colon, near the cecum. Unlike diverticula, they don’t cause sudden gushes. They leak slowly, over weeks or months. People with angiodysplasia usually don’t notice blood in their stool right away. Instead, they get tired. Pale. Short of breath. Their hemoglobin drops slowly. They’re diagnosed with iron-deficiency anemia first. Only after repeated tests do doctors find the source: those fragile, enlarged vessels. It’s strongly linked to aging. Over 80% of cases happen in people over 65. The average age at diagnosis is 72. There’s also a known link with aortic stenosis-a heart valve problem. When blood rushes through a narrowed valve, it can damage a clotting protein called von Willebrand factor. That makes the vessels more likely to bleed. Angiodysplasia accounts for 3% to 6% of lower GI bleeding cases today, though older studies reported higher numbers. That’s because we’ve gotten better at spotting other causes. Still, it’s the second most common reason for significant bleeding in the elderly after diverticula.

How Doctors Figure Out What’s Causing the Bleed

The first thing any hospital does when someone shows up with GI bleeding is stabilize them. Check blood pressure. Heart rate. Hemoglobin. Give fluids. Maybe blood. Then comes the workup. The BLEED criteria help predict who’s at risk for rebleeding: low blood pressure, long hospital stay, visible bleeding on scope, cancer or liver disease. If you score high, you need urgent action. Blood tests come first: CBC to check hemoglobin, coagulation panel to see if you’re clotting properly, type and crossmatch in case you need transfusion. Then-colonoscopy. This is the gold standard. Done within 24 hours of arrival, it finds the source in up to 85% of cases and can treat it at the same time. You don’t need a perfect prep. In emergencies, doctors give you IV fluids and erythromycin to clear out the colon faster. If the colonoscopy comes back clean? That’s when things get trickier. You’ve got what’s called “obscure” GI bleeding. Next step: capsule endoscopy. You swallow a tiny camera that takes pictures as it moves through your intestines. It finds the cause in about 62% of cases where colonoscopy didn’t. But capsule endoscopy isn’t perfect. If you have a narrowing in your bowel (maybe from scar tissue or cancer), the capsule can get stuck. That’s why some experts say to hold off until after other tests. Device-assisted enteroscopy-using a special scope with balloons-can reach deeper into the small bowel and finds the cause in 71% of cases, but it’s not available everywhere. CT angiography is another tool. It’s great if you’re bleeding fast-over half a milliliter per minute. It shows exactly where the blood is leaking. It’s non-invasive, quick, and works even if you’re too unstable for endoscopy.Treatment: What Works for Diverticula vs. Angiodysplasia

For diverticular bleeding, 80% of cases stop on their own. So the first step is usually just watching and supporting you-fluids, blood transfusions if needed. No surgery unless it keeps coming back. If it doesn’t stop? Endoscopy is the next move. Doctors use epinephrine injections to shrink the blood vessels, then heat (thermal coagulation) to seal them. This works in 85% to 90% of cases. But here’s the catch: 20% to 30% of people bleed again within a year. That’s why some patients need repeat scopes. For angiodysplasia, the treatment is different. The go-to method is argon plasma coagulation (APC). It’s like a precise, invisible laser that burns the abnormal vessels. It stops bleeding immediately in 80% to 90% of cases. But again-recurrence is common. Up to 40% of patients bleed again within two years. That’s where medications come in. Thalidomide, a drug once used for morning sickness, has shown surprising results. In a 2019 trial, taking 100 mg daily reduced transfusion needs by 70% in people with recurrent angiodysplasia. It’s not approved for this use, but many doctors prescribe it off-label. Octreotide, a hormone-like drug, is another option. Given as injections under the skin, it tightens blood vessels and reduces bleeding. It works in about 60% of cases. If all else fails? Surgery. For a single, confirmed angiodysplasia lesion in the cecum, a right hemicolectomy (removing the right side of the colon) is often recommended. For diverticula that keep bleeding in one segment, they remove just that part.What’s New in 2025?

AI is making colonoscopy better. New software can flag tiny angiodysplasia lesions that human eyes might miss. One 2022 study showed a 35% increase in detection rates. That means earlier diagnosis and fewer repeat scopes. New endoscopic clips are also helping. These are stronger, more precise, and can clamp down on bleeding diverticula with 92% success in European trials. They’re not yet standard everywhere, but they’re spreading. There’s also a major NIH-funded trial running right now (NCT04567891) testing thalidomide versus placebo for recurrent angiodysplasia. Results are expected in late 2024. If positive, this could become a first-line treatment.

What Happens After the Bleed?

Survival rates are actually pretty good. Five-year survival for diverticular bleeding is 78%. For angiodysplasia, it’s 82%. That’s because most people who bleed are older and have other health issues-not because the bleeding itself is deadly. But quality of life? That’s another story. People with recurrent angiodysplasia often go through what’s called a “diagnostic odyssey.” One survey found patients waited an average of 18 months and had three or more negative colonoscopies before being correctly diagnosed. That’s frustrating, exhausting, and expensive. Patients with diverticular bleeding tend to have one big scare, get treated, and move on. About 82% report it never comes back after one endoscopic treatment.When to Worry

Not every streak of blood means emergency. But if you have:- Large amounts of bright red blood

- Dizziness, lightheadedness, or fainting

- Heart rate over 100

- History of heart disease, kidney disease, or on blood thinners

Jigar shah

Interesting breakdown. I’ve seen both diverticula and angiodysplasia in my practice, and the key is always context. Angiodysplasia doesn’t scream-it whispers. By the time hemoglobin drops to 7, patients think they’re just ‘getting old.’

Colonoscopy’s still king, but I’ve had cases where capsule endoscopy caught what the scope missed-especially in the right colon. Just wish we had better prep protocols for elderly patients who can’t tolerate laxatives.

Sachin Bhorde

yo so i been seeing a lot of this in geriatric wards lately. diverticula bleed = loud and proud. angiodysplasia = silent assassin. got a guy last week with Hgb 6.2, no stool blood, just looked like he was gonna pass out. turns out it was 3 tiny AVMs in the cecum.

APC works like a charm but damn if they don’t come back. thalidomide? yeah i’ve prescribed it off-label. not pretty but beats transfusions every 3 weeks. docs need to stop treating this like it’s a one-off.

Joe Bartlett

Brits do this better. We’ve got the NHS protocol-colonoscopy within 12 hours, no waiting. No capsule nonsense unless you’re stable. Simple. Effective. Stop overcomplicating it.

Marie Mee

why is no one talking about the pharmaceutical companies pushing these endoscopic treatments? they make billions off repeat scopes and thalidomide prescriptions. the real cure is just stopping blood thinners but no one wants to say that because the money’s in the procedure

and what about the 5000 people who die every year from colon prep dehydration? they just say ‘it’s age’ but it’s the system

Naomi Lopez

While the clinical overview is accurate, the framing lacks epistemological nuance. The assumption that colonoscopy is the ‘gold standard’ reinforces a biomedical hegemony that pathologizes aging. Diverticula are not pathologies-they are anatomical adaptations to low-fiber diets over decades. The real crisis is not the bleeding, but the medicalization of normal aging physiology.

Thalidomide’s off-label use, while statistically significant, is a symptom of a system that prioritizes intervention over prevention. We need population-level dietary reform, not endoscopic band-aids. The NIH trial is promising, but it’s still framed within a curative paradigm rather than a preventative one. The data is solid, but the narrative is outdated.

Jody Patrick

My mom had angiodysplasia. Took 2 years and 4 colonoscopies before they found it. She was so tired all the time, we thought it was depression. If you’re older and always tired, get checked. Don’t wait.

Radhika M

Just had a patient with a 5cm diverticular bleed last week. No pain, just a bucket of blood. We did epinephrine + clip-stayed stable. New clips are game changers. Wish they were cheaper.

Philippa Skiadopoulou

Colonoscopy remains the cornerstone of diagnosis and intervention. Early intervention reduces rebleeding rates significantly. The data supporting endoscopic therapy is robust and reproducible. Avoidance of unnecessary imaging is prudent in unstable patients.

Pawan Chaudhary

Hey, if you’re reading this and you’re scared about blood in your stool-don’t panic. I’ve been there. My uncle had it, got treated, and now he’s hiking again at 78. It’s not the end. Doctors can fix this. Just go get checked.

Jonathan Morris

They never mention the CDC’s 2023 internal memo about how diverticula bleeding rates spiked 40% after the FDA approved erythromycin for colon prep. Coincidence? Or corporate influence on protocol? Look at the funding sources for those ‘successful’ endoscopic trials. Who paid for them?