When you pick up a prescription, you might not realize that the decision between a brand-name drug and its generic version isn’t just up to your doctor or pharmacist-it’s often shaped by rules set by your state government. Across the U.S., states have been quietly building systems to nudge patients, doctors, and pharmacies toward cheaper generic drugs. These aren’t random suggestions. They’re structured policies with real financial teeth: higher copays for brand names, mandatory pharmacist substitutions, and lists of approved drugs that insurers must cover first. The goal? To save billions without sacrificing health outcomes.

Why States Care About Generic Drugs

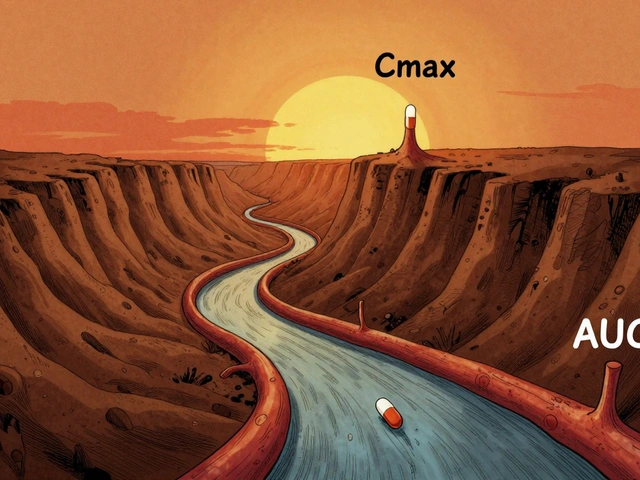

Generic drugs work the same way as brand-name drugs. Same active ingredients. Same safety standards. Same FDA approval. The only real difference? Price. A generic version of a drug can cost 80% less than the brand-name version. That’s not a small savings-it’s life-changing for people on fixed incomes, and it slashes state Medicaid budgets. Back in 1984, Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act, which made it easier for generic manufacturers to get approval. But that didn’t automatically mean doctors would prescribe them or patients would take them. States had to step in. By 2019, 46 out of 50 states had created Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs) for their Medicaid programs. These lists say: “We’ll cover this generic first. If you want the brand, you’ll need extra paperwork-or pay more.”How States Push Patients Toward Generics

There are three main tools states use to make generics more attractive:- Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs): These are the most common tool. States create a list of preferred generics. If your doctor prescribes a brand-name drug that’s not on the list, your pharmacy might refuse to fill it unless the doctor files a prior authorization form. In 20 states, these lists are reviewed every year. In 10, they’re reviewed quarterly. That means the list isn’t static-it changes as new generics hit the market or drug prices shift.

- Copay differentials: This is where patients feel the incentive directly. If your copay for a brand-name drug is $40 and the generic is $10, you’re saving $30 per prescription. Some states have pushed this gap even wider. In 2000, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that while pharmacy profits on generics and brands had nearly equalized, patient copays had grown significantly. That shift put the financial pressure where it matters most-on the person filling the prescription.

- Pharmacist substitution laws: This is where things get interesting. In some states, pharmacists can swap a brand-name drug for a generic without asking you. That’s called “presumed consent.” In others, they have to get your explicit permission first. A 2018 NIH study found that presumed consent laws increased generic dispensing by 3.2 percentage points. That might sound small, but multiply that across millions of prescriptions, and you’re talking about $51 billion in annual savings if every state adopted it.

Here’s the kicker: mandatory substitution laws-where pharmacists are forced to substitute regardless of patient preference-don’t actually move the needle much. Why? Because pharmacists already make more money dispensing generics. The real driver isn’t the law. It’s the patient’s wallet.

What Works Better: Incentives for Patients or Pharmacists?

You’d think giving pharmacists a bonus for dispensing generics would work. But research shows it doesn’t. The Department of Health and Human Services found that incentive programs aimed at pharmacists-like higher dispensing fees or penalties for prescribing brands when generics are available-have little impact. Why? Pharmacists are already motivated by profit. A $0.08 difference in dispensing fees between brand and generic in the late 1990s didn’t stop them from choosing generics. They were already doing it. The real leverage is on the patient. When you pay $30 more for a brand-name drug, you start asking questions. You talk to your doctor. You check if the generic is right for you. You might even switch. That’s why states are moving away from pushing providers and toward pushing consumers. The NIH study put it simply: a presumed consent law has the same effect on brand-name use as a $3 price increase on the brand drug. That’s powerful.

The Hidden Costs: When Generics Disappear

It’s not all smooth sailing. States have created a system that works-until it doesn’t. Generic drug manufacturers are caught in a trap. Under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, manufacturers must pay back a percentage of the drug’s price to the state. But here’s the problem: if the cost of ingredients goes up, or there’s a shortage, or the market gets crowded, the manufacturer can’t raise prices to cover it. Yet they still owe the same rebate. Avalere Health identified five scenarios where this happens:- Customer base shrinks

- Seasonal demand drops

- Input costs rise but CPI-U doesn’t reflect it

- Drug shortages

- Mature generic markets with too many competitors

In these cases, the drug becomes unprofitable in Medicaid. So manufacturers pull it. And suddenly, the generic your state counted on? Gone. You’re stuck with the brand-name version-or nothing at all. This isn’t hypothetical. It’s happened with antibiotics, insulin, and blood pressure meds. States thought they were securing access. Instead, they’re accidentally creating shortages.

The 340B Program and State Reimbursement Confusion

Another layer of complexity comes from the 340B Drug Pricing Program. Created in 1992, it lets safety-net hospitals and clinics buy drugs at steep discounts-20% to 50% off. But when Medicaid pays for those same drugs, it can’t reimburse more than the 340B ceiling price. That sounds fair. But in practice, it’s messy. In 2016, CMS forced states to update their reimbursement rules for 340B drugs by April 1, 2017. Many didn’t know how to calculate it. Some used the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP). Others used Best Price. Some used Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists. The result? Pharmacies got paid inconsistently. Some made money. Some lost money. And some stopped filling 340B prescriptions altogether. This isn’t just a paperwork problem. It’s a access problem. If a pharmacy can’t get paid fairly, it won’t stock the drugs. And if it doesn’t stock them, patients go without.

What’s Next? The Medicare Drug List

The federal government is watching. In 2023, CMS announced a pilot program called the Medicare $2 Drug List. It’s simple: for certain low-cost generics, Medicare Part D beneficiaries pay just $2 per prescription-no matter the brand. No prior authorization. No copay tiers. Just $2. It’s a game-changer. If it works, states will copy it. Why? Because it removes all the friction. No forms. No debates. No confusion. Just a clear, simple incentive: pay $2, get the generic. States are already testing similar ideas. Some have capped copays at $5 for generics. Others have eliminated copays entirely for certain chronic condition drugs. The trend is clear: simplicity wins. The more complicated the system, the more people fall through the cracks.What You Can Do

If you’re on Medicaid or have a high-deductible plan, ask your pharmacist: “Is there a generic for this? Is it on my plan’s preferred list?” If you’re paying more than $10 for a generic, you might be eligible for a lower copay. Some states have programs that let you appeal your copay if the generic isn’t working for you. Don’t assume your doctor knows the latest state rules. Ask. Be proactive. The system works best when you’re part of it.Why This Matters Beyond the Budget

This isn’t just about saving money. It’s about fairness. Generic drugs make treatment possible for people who otherwise couldn’t afford it. A diabetic who can’t afford insulin might skip doses. A heart patient who can’t pay for blood pressure meds might end up in the ER. Generic incentives help prevent that. But they can’t work if the system breaks. If manufacturers pull out because the math doesn’t add up, then the savings disappear-and so does access. The challenge for states isn’t just to push for generics. It’s to build a system that keeps them available, affordable, and reliable.States have the tools. They’ve got the data. They know what works. Now they just need to balance short-term savings with long-term sustainability. Because the goal isn’t just to cut costs. It’s to keep people healthy.

Do all states have generic prescribing incentives?

No, but most do. As of 2019, 46 out of 50 states had Preferred Drug Lists for Medicaid. Only 15 states and Puerto Rico had formal copay adjustment laws as of 2022. Every state allows pharmacist substitution to some degree, but the rules vary widely-from presumed consent to explicit permission.

Can my pharmacist switch my brand-name drug without asking me?

It depends on your state. In 11 states and D.C., pharmacists can substitute generics without your permission-that’s presumed consent. In the other 39, they must ask you first. Check your state’s pharmacy board website or ask your pharmacist directly. If you don’t want a generic, you have the right to refuse it, even in presumed consent states.

Why is my generic drug suddenly unavailable?

It’s often due to Medicaid rebate rules. If the cost of making the drug goes up but the manufacturer can’t raise the price (because of rebate caps), they may stop selling it in Medicaid markets. This has happened with antibiotics, thyroid meds, and even some heart medications. If your generic disappears, ask your doctor about alternatives or whether the brand is covered under an exception.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They must also meet the same strict manufacturing standards. The only differences are inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes), which rarely affect how the drug works. Millions of people use generics safely every day.

Will the Medicare $2 Drug List affect my state’s Medicaid program?

Not directly-but likely indirectly. If the $2 model proves successful in Medicare, states will see it as a proven, simple way to boost generic use and cut costs. Many are already experimenting with similar flat copays. The federal model could become the blueprint for future state policies, especially as Medicaid programs face growing budget pressure.

Jeremy Hernandez

They say generics are just as good but let me tell you something - the fillers in those cheap pills are what’s making people sick. I’ve seen it. My cousin went from feeling fine to zombified after switching. The FDA doesn’t test the junk they put in there. Big Pharma’s got the government in their pocket, and now states are just doing their dirty work for them. You think this is saving money? It’s just creating a new kind of addiction - to undercooked medicine.

Tarryne Rolle

It’s ironic, isn’t it? We’ve built a system that forces people to choose the cheapest option in the name of compassion. But compassion isn’t about cost-cutting - it’s about dignity. If a person needs a brand-name drug because their body reacts differently, forcing them into a generic is just economic eugenics dressed up as policy. We’re not saving lives. We’re optimizing spreadsheets while people suffer in silence.

Kyle Swatt

Look man - the real story here isn’t the generics or the copays or even the rebates. It’s the fact that we’ve turned healthcare into a fucking game of Monopoly where the players don’t even get to roll the dice. The system’s rigged from the start - manufacturers get squeezed, pharmacists get confused, patients get scared. And the only ones who win are the ones who never had to pick up a prescription in the first place. We need to stop pretending this is about health. It’s about power. And someone’s got to break the board.

Deb McLachlin

While the article presents a comprehensive overview of state-level generic drug incentives, it is worth noting that the absence of longitudinal data on clinical outcomes among patients transitioned to generics limits the robustness of the conclusion that health outcomes are unaffected. Furthermore, the variability in state implementation protocols introduces significant confounding variables that are not adequately addressed. A standardized national framework may be more effective than the current patchwork system.

saurabh lamba

bro why u even care? generic is generic. if u need brand name u rich. if u poor u take generic. problem solved. also why u think pharma care is about health? its about money. always was. always will be. 😒

Kiran Mandavkar

Let’s be honest - this whole system is a third-world workaround for a first-world problem. You don’t fix a broken healthcare system by forcing people into cheaper pills. You fix it by dismantling the pharmaceutical cartel that prices insulin at $300 and calls it ‘innovation.’ This isn’t policy. It’s a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage. And now we’re pretending the bleeding stopped because the gauze is cheaper.

Eric Healy

they say generics are safe but i seen a guy on reddit say his blood pressure went nuts after switching to the generic version of lisinopril. and now he’s in the hospital. and the doc just shrugged. the FDA approves everything but they dont test real life. its all lab rats and paperwork. this whole system is a joke. i dont trust it. not one bit.

Shannon Hale

OH MY GOD. I CAN’T BELIEVE THIS IS STILL HAPPENING. I had to fight my pharmacy for THREE WEEKS because they tried to swap my brand-name seizure med for a generic. I had SEIZURES. Not ‘kinda weird dizziness’ - full-on convulsions. And now they’re pushing this as a ‘savings model’? This isn’t healthcare. It’s a death sentence for people who don’t have lawyers on speed dial. Someone needs to burn this whole system down.

Bill Machi

Let me tell you something about this country - we don’t need more incentives. We need accountability. The federal government lets drug companies price gouge, then turns around and tells states to fix it by making patients pay more. It’s not a policy. It’s a betrayal. And you think this is patriotism? This is surrender. We’re letting corporations bleed us dry and calling it ‘smart economics.’ Shameful.

Elia DOnald Maluleke

Indeed, the structural paradox embedded within this policy architecture is not merely fiscal - it is ontological. The very mechanism designed to ensure accessibility - the Medicaid rebate formula - inadvertently incentivizes scarcity. When profit margins collapse under the weight of fixed rebates, the market does not adapt - it evaporates. Thus, the policy that seeks to democratize pharmaceutical access becomes the architect of its own collapse. One must ask: Is this governance, or is it a form of institutionalized self-sabotage?