Diabetic ketoacidosis, or DKA, isn’t just a scary term you hear in diabetes education. It’s a medical emergency that can kill you if you wait too long. Every year in the U.S., more than half a million hospital stays are caused by DKA. And while it’s most common in people with type 1 diabetes, it can also hit those with type 2 - especially if they skip insulin, get sick, or are on certain newer medications like SGLT2 inhibitors. The worst part? Many people don’t realize they’re in danger until it’s too late.

What Happens in Your Body During DKA?

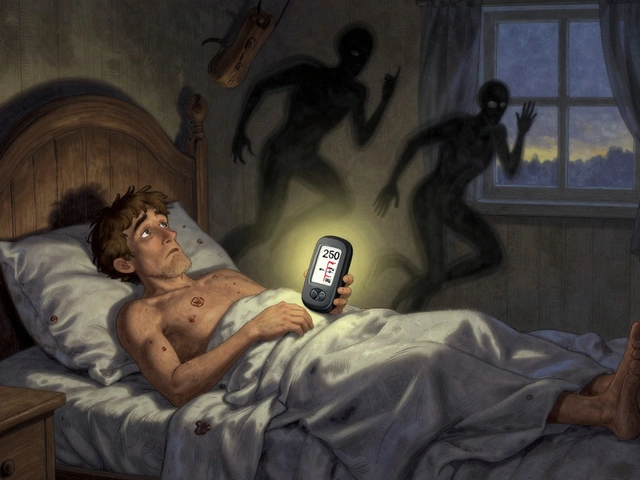

When you don’t have enough insulin, your body can’t use sugar for energy. So it starts breaking down fat instead. That process creates acids called ketones. Too many ketones make your blood too acidic. At the same time, your blood sugar skyrockets - often above 250 mg/dL. But here’s the twist: about 10% of DKA cases happen with blood sugar under 250 mg/dL. This is called euglycemic DKA, and it’s often missed because people assume low sugar means they’re safe.

The body tries to flush out the excess sugar and ketones by peeing nonstop. That leads to severe dehydration. Your kidneys can’t keep up. Electrolytes like potassium, sodium, and chloride get washed away. Your breathing gets deep and fast - a sign your body is trying to blow off acid. And if things keep going, you start to feel confused, then drowsy, then unconscious.

Early Warning Signs You Can’t Ignore

DKA doesn’t come out of nowhere. It builds over hours. The first signs are easy to brush off - especially if you’re sick or stressed.

- Extreme thirst - You’re drinking 4 to 6 liters of water a day and still parched.

- Frequent urination - You’re running to the bathroom every hour, day and night.

- Dry mouth - Your tongue feels like sandpaper. This happens in nearly 9 out of 10 cases.

- Blood sugar over 250 mg/dL - Check it. If it’s high and you feel off, don’t wait.

These aren’t just inconveniences. They’re your body screaming for help. If you have two or more of these and your blood sugar is high, test for ketones. Now. Use a blood ketone meter if you have one. If it reads above 3 mmol/L, go to the ER. Don’t call your doctor first. Don’t wait until morning.

Progression: When It Gets Dangerous

After 12 to 24 hours, things get serious. The early signs worsen, and new ones appear.

- Nausea and vomiting - You can’t keep food or water down. This happens in 75% of cases.

- Abdominal pain - It feels like a stomach bug or appendicitis. In fact, nearly half of adults with DKA are initially misdiagnosed with gastroenteritis.

- Fatigue and weakness - You can’t get out of bed. Your grip feels weak. You’re exhausted even after sleeping.

- Fruity-smelling breath - It smells like nail polish remover or overripe apples. Clinicians recognize it instantly.

- Deep, rapid breathing - This is called Kussmaul respirations. It’s your body’s last-ditch effort to correct the acid in your blood.

If you see these signs, you’re in a critical zone. Confusion, disorientation, or drowsiness mean your brain is being affected by the acid. This is not something to manage at home. You need IV fluids, insulin, and constant monitoring - and you need them now.

What Happens in the Hospital?

DKA doesn’t get better with rest or over-the-counter meds. Hospital treatment is intense but life-saving.

The first hour is all about fluids. You’ll get 1 to 1.5 liters of salt water (0.9% sodium chloride) through an IV. This rehydrates you and helps your kidneys flush out ketones. After that, fluids continue at a slower rate - but you’ll likely get 4 to 8 liters total in the first 24 hours.

Insulin comes next. Not a shot. Not pills. A continuous IV drip. Doctors start with a small IV bolus, then keep the drip going at a steady rate. The goal? Lower your blood sugar by 50 to 75 mg/dL per hour. Too fast, and you risk brain swelling - especially in kids. That’s why speed matters, but not too much speed.

Electrolytes are just as important. Even if your blood test shows normal potassium, your body is totally depleted. You’ll get potassium through the IV, usually 20 to 30 mEq per hour. Sodium and chloride are monitored closely too. You can’t fix DKA without balancing these.

Bicarbonate? Rarely used. Only if your blood pH drops below 6.9 - which is extremely rare. Most hospitals stopped using it years ago because it doesn’t help and can cause harm.

Doctors also look for what triggered the DKA. Was it an infection? A missed insulin dose? A new diagnosis? You’ll likely get a chest X-ray, urine test, and blood cultures. Treating the trigger is half the battle.

How Long Do You Stay in the Hospital?

Most people stay 2.5 to 4 days. But it depends on how bad it was when you arrived. If your blood pH was 7.0 or lower, you’re likely looking at 3.5 to 4 days. If it was 7.1 or higher, you might be out in 2 days.

You won’t be discharged until your ketones are under 0.6 mmol/L, your bicarbonate is above 18 mmol/L, and your pH is back to normal - and stays there for two checks. Rushing this step is why 12% of people end up back in the hospital within three days.

What You Can Do to Prevent DKA

DKA is preventable - if you know the signs and act fast.

- Check ketones anytime your blood sugar is over 240 mg/dL, especially if you’re sick.

- If you use an insulin pump, switch to injections when you’re ill. Pump failures cause 35% of DKA cases in pump users.

- Never skip insulin, even if you’re not eating. Your body still needs it.

- Use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM). People with CGMs have 76% fewer DKA episodes because alerts catch problems early.

- If you’re on an SGLT2 inhibitor (like Jardiance or Farxiga) and have type 1 diabetes, talk to your doctor about ketone monitoring. These drugs increase risk of euglycemic DKA.

And if you’re worried about insulin cost - you’re not alone. Nearly 3 in 10 type 1 patients say they’ve rationed insulin because of price. That’s a direct path to DKA. Reach out to patient assistance programs. Insulin shouldn’t be a luxury.

Why People Miss the Signs

Surveys show 68% of people wait more than 6 hours after symptoms start before seeking help. Why? They think it’s just the flu. Or they’re scared of the ER. Or they don’t know ketones are dangerous.

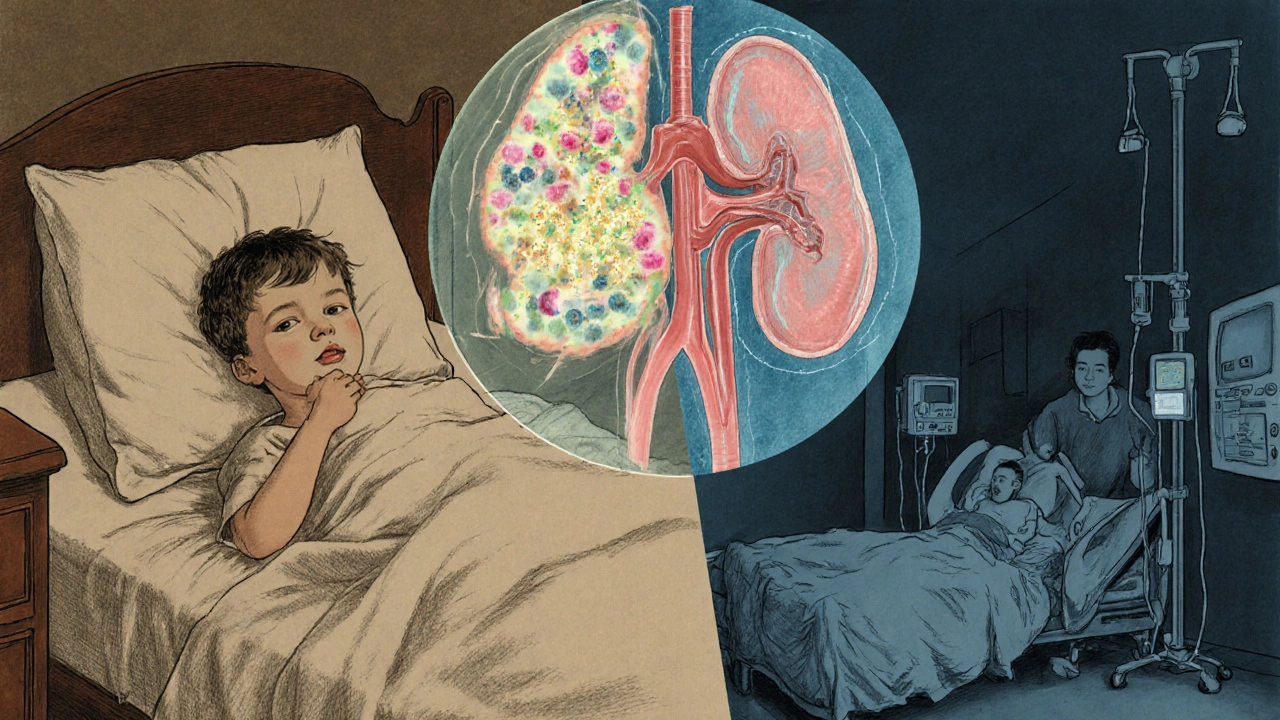

One of the biggest dangers is misdiagnosis. Emergency rooms see hundreds of people with vomiting and stomach pain every day. DKA often gets labeled as gastroenteritis. That’s deadly - especially for kids who haven’t been diagnosed with diabetes yet. About 1 in 5 DKA cases in children is their first sign of type 1 diabetes.

That’s why the American College of Emergency Physicians now recommends that every diabetic with blood sugar over 250 mg/dL gets a point-of-care ketone test. In hospitals that followed this rule, missed DKA cases dropped by 37%.

The Future: Prevention Is Getting Smarter

New tech is making DKA harder to catch off guard. In 2023, the FDA approved the first algorithm that predicts DKA 12 hours before it happens - using data from CGMs. It’s already being added to systems like Tidepool Loop. This could cut DKA rates dramatically.

Meanwhile, global efforts are saving lives in low-income countries. Simple protocols using subcutaneous insulin - instead of IV - have cut mortality in sub-Saharan Africa from 15% to 6%. That’s progress.

But here’s the hard truth: DKA cases in the U.S. are still rising by over 5% every year. Why? Lack of access. Uninsured patients are more than three times as likely to get DKA. That’s not a medical problem. It’s a systemic one.

You can’t fix the system overnight. But you can protect yourself. Know the signs. Test ketones. Act fast. Your life depends on it.

What are the first signs of diabetic ketoacidosis?

The earliest signs include extreme thirst, frequent urination, dry mouth, and blood sugar over 250 mg/dL. These can develop within hours. If you have two or more of these and your glucose is high, check for ketones immediately. Don’t wait for vomiting or confusion - those are later, more dangerous signs.

Can you have DKA with normal blood sugar?

Yes. This is called euglycemic DKA, and it accounts for about 10% of cases. It’s more common in people using SGLT2 inhibitors (like Jardiance or Farxiga) or during pregnancy. Even if your blood sugar is under 250 mg/dL, high ketones and low pH mean you’re still in DKA. Don’t rely on glucose alone - always test ketones if you feel unwell.

Is DKA only for people with type 1 diabetes?

No. While 80% of DKA cases occur in type 1 diabetes, it can also happen in type 2 diabetes - especially during serious illness, infection, or if insulin is stopped. People on SGLT2 inhibitors are also at higher risk, even if they don’t usually need insulin. Anyone with insulin deficiency can develop DKA.

How is DKA treated in the hospital?

Treatment involves three key steps: fluids (IV saline to rehydrate), insulin (continuous IV drip to lower ketones and glucose), and electrolyte replacement (especially potassium). Blood sugar is lowered slowly - no more than 75 mg/dL per hour - to avoid brain swelling. Ketones, pH, and electrolytes are monitored hourly until stable. Underlying causes like infection are treated at the same time.

Can you treat DKA at home?

No. DKA requires hospital care. Even if you feel okay, your body is in acidosis and dehydrated. Home treatment with extra insulin or fluids won’t fix the electrolyte imbalance or prevent complications like brain swelling. Delaying hospital care increases your risk of death by 15% per hour after the first two hours.

How can I prevent DKA?

Check your blood sugar and ketones regularly, especially when sick or stressed. Use a continuous glucose monitor with ketone alerts if possible. Never skip insulin, even if you’re not eating. If you use an insulin pump, switch to injections during illness. Know your triggers - infection, missed doses, or new medications - and act fast if symptoms appear.

Why do some people get misdiagnosed with DKA?

DKA symptoms like vomiting, abdominal pain, and fatigue mimic stomach flu or food poisoning. Emergency staff often mistake it for gastroenteritis - especially in adults or children with no known diabetes history. This is dangerous because untreated DKA can lead to coma or death. Always ask for a ketone test if you’re diabetic and feeling sick with high blood sugar.

What’s the most dangerous complication of DKA?

Cerebral edema - swelling of the brain - is the leading cause of death in children with DKA, occurring in 0.5% to 1% of cases with up to 24% mortality. It’s rare in adults but still possible. It’s caused by rapid fluid shifts during treatment. That’s why doctors carefully control how fast fluids and insulin are given. Slower correction saves lives.

Jennifer Walton

Been there. First time I checked ketones, it was 4.2. Thought it was just a bad sugar spike. Turned out I was dehydrated, shaking, and couldn’t stand up. ER saved me. Don’t wait for the fruity breath. If you’re thirsty and peeing nonstop, test. Now.

It’s not dramatic. It’s biology.

Kihya Beitz

Wow. Another ‘you’re gonna die if you blink’ post. Can we please stop treating diabetes like a horror movie? I’ve had T1 for 18 years. I’ve had ketones at 2.8 and went to bed. I’m still here.

Stop scaring people into panic mode. Not everyone’s a walking DKA waiting to happen.

Jessica Chambers

@Kihya Beitz I get it, you’re tired of fear-mongering. But I’ve seen two friends in the ICU from ‘just skipping one dose.’

It’s not fear. It’s facts. And if you’re gonna roll the dice, at least know the odds. 😅

Shyamal Spadoni

They dont want you to know this but DKA is a scam pushed by big pharma and the hospital-industrial complex. Why do you think they make you pay for ketone strips but insulin is ‘free’ in Canada? Its all about control. They want you dependent. The real cause of DKA is glyphosate in your water and the government forcing insulin on people who dont need it. I tested my ketones once and my glucose was 180 but I felt fine. They lied about the 250 threshold. Its a lie. The WHO is in on it. I read it on a forum in 2017 and its been true ever since. They dont want you to know you can just drink lemon water and pray. I did. I survived. They dont tell you that.

Also CGMs are tracking you. The blue light is a signal. Dont trust the numbers. Trust your gut. Your gut knows.

Ogonna Igbo

In Nigeria we treat DKA with subcutaneous insulin and clean water. No IVs. No fancy machines. Just one nurse and a lot of faith. Why are Americans so weak? You have all this technology and still you die from a simple thing like dehydration? You pay $500 for a test strip and still you don’t check? This is why your system is broken. We fix this with discipline. You fix it with bills.

Stop acting like you’re special. We’ve been doing this for decades with no insurance. Your problem is not medicine. It’s greed.

BABA SABKA

Let’s be real - DKA isn’t a mystery. It’s a failure of system design. If insulin cost $10 a vial instead of $300, 80% of these cases wouldn’t exist. The medical community talks about ketones like they’re the enemy. But the real enemy is profit-driven healthcare. I’ve seen people ration insulin because their copay is $120. That’s not diabetes. That’s capitalism.

And yeah, SGLT2 inhibitors? They’re dangerous as hell for type 1s. But they’re profitable. So they get pushed. Doctors don’t even know the risks half the time. You think they’re educating patients? Nah. They’re hitting quotas.

This isn’t about ‘knowing the signs.’ It’s about fixing the system that makes signs even necessary.

Chris Bryan

They’re lying about the 10% euglycemic DKA stat. That’s a CDC cover-up. Why? Because if people knew you could go into acidosis with normal glucose, they’d realize the whole glucose-centric model is flawed. The FDA is in bed with Abbott and Dexcom. CGMs are surveillance tools. They’re selling your data to insurers. That’s why they push them so hard. You think they care about your life? No. They care about your subscription fee.

And don’t get me started on IV fluids. That’s just saline. You can get that at the grocery store. Why do you need a hospital? They’re milking you. Always.

Jonathan Dobey

DKA isn’t just a metabolic crisis - it’s a metaphysical rupture. The body, in its ancient wisdom, is screaming: ‘You have abandoned the sacred rhythm of insulin!’ We live in a world of glucose obsession, where the divine balance between fuel and flow has been replaced by algorithmic surveillance and corporate insulin cartels.

That fruity breath? That’s not acetone. That’s the scent of modernity’s failure - the smell of a civilization that turned a physiological necessity into a commodified, insurance-locked ritual.

And yet… we still cling to our CGMs like digital rosaries, begging for alerts from machines that don’t understand the soul of blood.

Perhaps the cure isn’t in IV drips or potassium boluses - but in relearning how to listen. To the body. To the silence between the beeps.

Or maybe… we’re just all a little too addicted to being saved.