The Federal Circuit Court doesn’t just hear patent cases-it decides how long drugs stay off the market, how much generic companies spend on lawsuits, and whether a new dosing schedule can be patented at all. If you’re in pharma, whether you make brand-name drugs or generics, this court’s rulings touch your bottom line. And unlike other federal courts, it’s the only one in the country that handles every single patent appeal. That means what it says on pharmaceutical patents? That’s the law.

Why the Federal Circuit Owns Pharmaceutical Patents

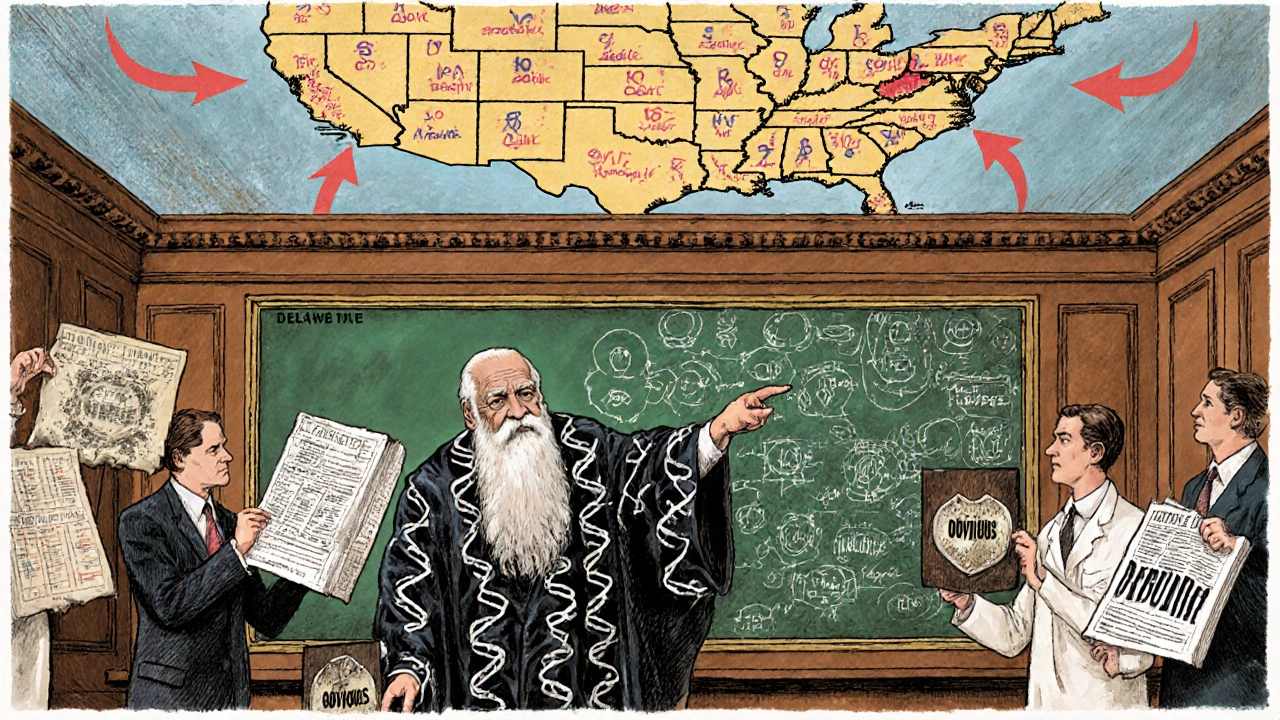

Created in 1982, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit was designed to fix a mess: patent law was being interpreted differently across 12 regional courts. One judge in Texas might say a drug dosage is patentable. Another in California might say it’s obvious. That chaos hurt innovation and created legal uncertainty. So Congress gave all patent appeals to one court-the Federal Circuit. No exceptions. Not for biotech, not for software, not for pharmaceuticals. If it’s a patent case, it goes here. This isn’t just about convenience. It’s about consistency. When a generic drug company files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA to sell a cheaper version of a brand drug, the brand company can sue for patent infringement. That lawsuit can happen anywhere. But when it gets appealed? It always lands in the Federal Circuit. That’s why Delaware, a tiny state with no big pharma companies, became the most popular place to file these lawsuits. Why? Because the Federal Circuit’s rulings are predictable. And if you’re a patent holder, predictability means you can plan your legal strategy around winning.ANDA Filings and the Nationwide Jurisdiction Rule

In 2016, the Federal Circuit changed the game with its ruling in Mylan v. In re: Celgene. The court said: if you file an ANDA with the FDA, you’re not just asking to sell a drug in one state-you’re asking to sell it everywhere. That means, legally, you’ve made contact with every state in the U.S. That’s enough to give any court in the country jurisdiction over you. Before this, generic companies could argue they were only subject to lawsuits in their home state. After this decision? A patent holder could sue a generic company based in Texas in Delaware, New Jersey, or even California. The result? A flood of lawsuits in Delaware. By 2023, 68% of all ANDA patent cases were filed there. That’s up from 42% just a decade earlier. Why does this matter? Because Delaware courts are known to be friendly to patent holders. Generic companies now spend more on legal fees just to fight jurisdiction than they do on developing the drug. And that’s exactly what the Federal Circuit intended: to make patent enforcement easier for innovators.The Orange Book and What Gets Listed

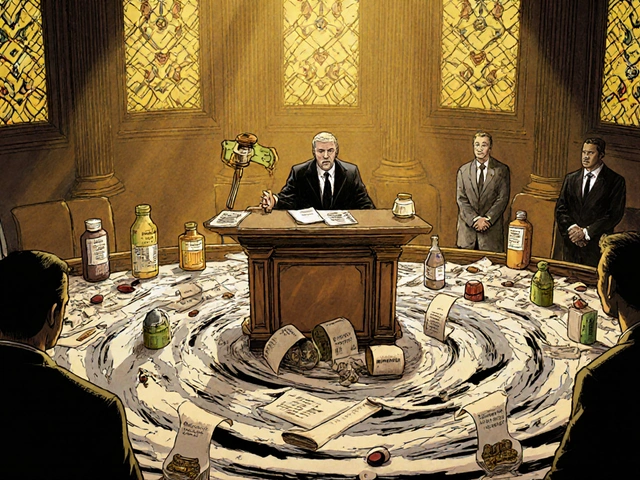

The Orange Book-officially called Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations-is the FDA’s list of patents tied to brand-name drugs. If a patent isn’t listed there, a generic company can’t be sued for infringing it when it files an ANDA. In December 2024, the Federal Circuit ruled in Teva v. Amneal that only patents that actually claim the drug itself can be listed. Not patents on packaging. Not patents on manufacturing methods. Not patents on methods of use unless they’re directly tied to the drug’s chemical structure. This decision forced companies to clean up their Orange Book listings. Some had listed patents that didn’t even mention the active ingredient. Those got removed. And once a patent is removed, the 30-month stay on generic approval ends. That’s a big deal. A 30-month delay can mean hundreds of millions in lost sales for a blockbuster drug. Now, pharmaceutical companies spend weeks mapping each patent to the exact drug claim before submitting it to the FDA. Legal teams do “patent-drug claim mapping” exercises. It adds 17 business days to the pre-filing process, according to a 2024 survey of top pharmaceutical firms. But it’s necessary. Miss the mark, and your patent gets stripped from the Orange Book. No more litigation shield.

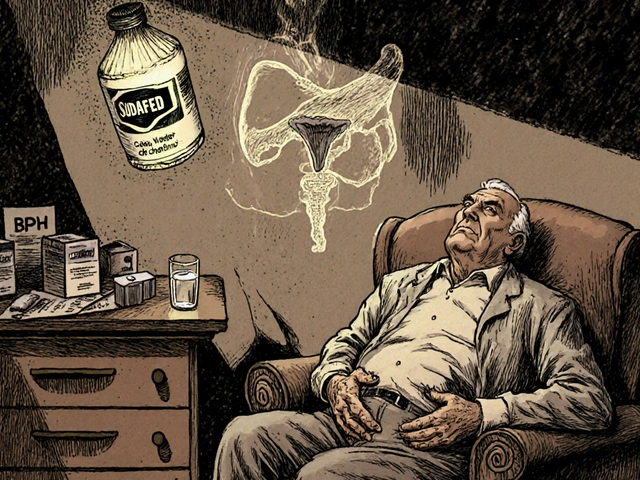

Dosing Regimens: The New Patent Death Zone

One of the biggest battlegrounds in pharma patents is dosing. Can you patent a new way to take a drug? Like “take one pill daily instead of twice a day”? For years, companies tried. They called them “method of treatment” patents. They were cheap to file. And they extended exclusivity without developing a new molecule. Then came the April 2025 decision in ImmunoGen v. Sarepta. The Federal Circuit said: no. If the drug itself is already known, changing the dose isn’t enough to make it patentable. The court ruled that the “reasonable expectation of success” standard applies. If a skilled scientist could reasonably expect the same results with a different dosing schedule, then it’s obvious-and not patentable. Judge Lourie put it plainly: “Because both sides admitted that the use of IMGN853 to treat cancer was known in the prior art, the only question to resolve was whether the dosing limitation itself was obvious.” This decision sent shockwaves through the industry. A 2024 Clarivate analysis showed pharmaceutical companies cut their secondary patent filings for dosing innovations by 37% after this ruling. Instead of filing 10 patents on dosing schedules, they’re now investing 22% more in discovering entirely new compounds. That’s a major shift in R&D strategy. Patent attorneys now spend 25-40% more time on dosing claims, adding clinical data that shows unexpected benefits. If you’re claiming a new dose, you can’t just say “it’s easier.” You have to prove it’s safer, more effective, or reduces side effects in a way prior art didn’t suggest. The bar is high. And the Federal Circuit isn’t lowering it.Standing: Who Can Even Sue?

You can’t just walk into court and say, “I think this patent is invalid.” You need standing. You need to show you’re actually hurt by it. In May 2025, the court ruled in Incyte v. Sun Pharmaceutical that companies developing a generic version of a drug must have concrete, immediate plans to market it. A vague intention isn’t enough. You need Phase I clinical trial data, manufacturing agreements, or FDA communication records. Without it, the court says you don’t have standing to challenge the patent. This has created a catch-22 for generic companies. To challenge a patent, you need to invest in development. But if you invest too early, you risk being sued for infringement. So many wait until they’re close to filing an ANDA. That delays market entry. And it’s exactly what patent holders want. Judge Hughes, in his concurrence, warned that this standing rule is “disproportionately harming generic drug developers.” He noted that companies are being forced to spend millions before they even know if their product will infringe. His comments sparked the “Patent Quality Act of 2025,” introduced by Senators Tillis and Coons, which could change standing rules specifically for pharma.

How This Court Shapes the Market

The Federal Circuit’s decisions don’t just affect lawyers. They affect patients, drug prices, and innovation. Between 2016 and 2023, patent litigation against generic companies rose 22%. The average cost per ANDA case jumped from $5.2 million to $8.7 million. That’s money that doesn’t go into R&D or lower prices. It goes to law firms. Biosimilars-the generic version of biologic drugs-are also feeling the impact. Since the 2020 ruling in Samsung Bioepis, biosimilar patent litigation has surged 300%. The court extended the same jurisdiction rules from ANDAs to biosimilars. That means the same legal risks apply. Meanwhile, brand companies have seen their core compound patents hold up 82% of the time in challenges. But their secondary patents-on dosing, packaging, or methods-are falling at record rates. The court is clear: innovation means new molecules. Not new pills.What This Means for You

If you’re a brand company: focus on strong compound patents. File them early. List them correctly in the Orange Book. Don’t waste money on weak dosing patents. They won’t survive. If you’re a generic company: document everything. Clinical trials, manufacturing plans, FDA correspondence. You need proof of standing before you challenge a patent. And if you file an ANDA? You’re now subject to lawsuits anywhere in the U.S. Plan your legal strategy like you plan your supply chain. If you’re a patent attorney: the rules are clear. Dosing claims need clinical proof. Jurisdiction is nationwide. Standing requires action, not intent. The Federal Circuit isn’t changing its mind. You need to adapt.What’s Next?

The court isn’t slowing down. More rulings on biosimilars, digital therapeutics, and AI-driven drug discovery are coming. The “Patent Quality Act of 2025” could change standing rules. But until then, the Federal Circuit remains the final word. It’s not just a court. It’s a gatekeeper. It decides when a drug can be sold, how much it costs, and who gets to make it. And for anyone in pharmaceuticals, understanding its authority isn’t optional. It’s survival.Why does the Federal Circuit have exclusive authority over pharmaceutical patent cases?

The Federal Circuit was created by Congress in 1982 to unify patent law across the U.S. Before that, different regional courts interpreted patent rules differently, causing confusion and inconsistent outcomes. The Federal Courts Improvement Act gave it exclusive jurisdiction over all patent appeals, including those involving pharmaceuticals, to ensure consistent legal standards nationwide. This means every patent case, no matter where it starts, ends up here on appeal.

Can a generic drug company be sued in any state after filing an ANDA?

Yes. Since the 2016 Mylan decision, the Federal Circuit ruled that filing an ANDA with the FDA shows intent to market the drug nationwide. That creates personal jurisdiction in any U.S. federal court, even if the company has no physical presence there. This is why Delaware became the top venue for patent lawsuits-it’s seen as favorable to patent holders and has a specialized court system for these cases.

What’s the Orange Book, and why does it matter for patent lawsuits?

The Orange Book is the FDA’s official list of patents tied to brand-name drugs. Generic companies can only be sued for infringing patents listed there. In 2024, the Federal Circuit ruled that only patents that actually claim the drug’s chemical structure can be listed. Patents on packaging, manufacturing, or methods of use without direct claims to the drug were removed. This forces companies to be precise and reduces “evergreening” tactics.

Can you patent a new dosage schedule for an existing drug?

It’s extremely difficult now. After the April 2025 ImmunoGen decision, the Federal Circuit said that changing the dose of a known drug isn’t enough for a patent unless there’s unexpected benefit-like significantly improved safety or efficacy not suggested by prior art. Minor changes, like switching from twice-daily to once-daily dosing, are now routinely rejected as obvious. This has led to a 37% drop in secondary patent filings for dosing regimens.

Do I need to be developing a drug to challenge a patent in court?

Yes. Since the May 2025 Incyte decision, you need “Article III standing,” meaning you must show concrete, immediate plans to develop or market a product that might infringe the patent. Vague intentions or market research aren’t enough. You need Phase I clinical trial data, manufacturing agreements, or FDA correspondence proving active development. Without it, the court will dismiss your case for lack of standing.

Evelyn Shaller-Auslander

sooo... if i get this right, they’re basically making it harder for generics to even get started? like, you gotta have clinical trials lined up just to *ask* if the patent’s legit? that’s wild.

Gus Fosarolli

Delaware is basically the patent court’s VIP lounge. No pharma giants there, just lawyers in suits sipping coffee while generic companies burn millions on jurisdictional chess. 🤡

Nirmal Jaysval

fr tho, this whole system is rigged. patent trolls dont make drugs they just sit on papers and scare ppl. and now they got the fed circuit on their side. sad.

Emily Rose

Y’all are missing the real issue: this isn’t about patents-it’s about access. If a 70-year-old can’t afford their med because a company spent $10M on a dumb dosing patent, we’ve lost the plot. Pharma’s not here to save lives anymore. It’s here to maximize shareholder value. Period.

Benedict Dy

The Federal Circuit’s rulings are not merely legal-they’re economic weapons. The 82% uphold rate on compound patents reveals a court system that prioritizes rent-seeking over innovation. Meanwhile, the 37% drop in dosing patents is a market signal: stop gaming the system. The market is adapting. The regulators? Not so much.

John Power

As someone who’s worked in generics for 12 years, this is brutal. We used to be able to challenge patents early and save everyone time. Now we’re stuck waiting until we’ve spent $2M on clinical trials just to get a shot in court. It’s a trap. And yeah, I know the court says ‘standing’-but what’s the point of competition if you have to risk bankruptcy to even start?

Scott McKenzie

Orange Book cleanup is long overdue. I’ve seen patents listed for ‘blue pill packaging’ and ‘uses with a spoon’ 😅. Glad the court finally said ‘nope.’ Real innovation > legal loopholes. 🙌

Jeremy Mattocks

Let’s not forget the ripple effects here. When you kill off secondary patents on dosing, you’re not just changing the law-you’re changing R&D culture. Companies are shifting from ‘how can we extend this drug?’ to ‘how can we find something truly new?’ That’s huge. It’s like the whole industry is being forced to grow up. And honestly? It’s about time. The days of slapping a new pill schedule on an old molecule and calling it innovation are over. Now they’ve got to actually invent something. That’s good for patients. That’s good for science. That’s good for the future. Even if it hurts the lawyers.

Paul Baker

so the fed circuit is like the god of pharma patents and now they say if you wanna sue someone for a new dose you gotta prove it actually works better?? lol imagine that 🤯

Zack Harmon

THIS IS A DISASTER. THEY’RE KILLING INNOVATION. DO YOU KNOW HOW MUCH MONEY WE SPENT ON THOSE DOSING PATENTS?? NOW WE’RE ALL JUST SITTING HERE LIKE CHICKENS WITH OUR HEADS CUT OFF. THE FED CIRCUIT IS A MONSTER. THEY DON’T UNDERSTAND PHARMA. THEY JUST LOVE WRITING OPINIONS.

Jeremy S.

Real talk: the system’s broken, but the court’s trying to fix it. We need more transparency, not more lawsuits.