When you’re breastfeeding and need to take a medication, it’s natural to worry: is this drug going to hurt my baby? The truth is, most medications are safe. But not all. And figuring out which ones are okay isn’t as simple as just avoiding pills. It’s about understanding how drugs move from your bloodstream into your milk, what factors make some drugs riskier than others, and how to use them wisely.

How Medications Get Into Breast Milk

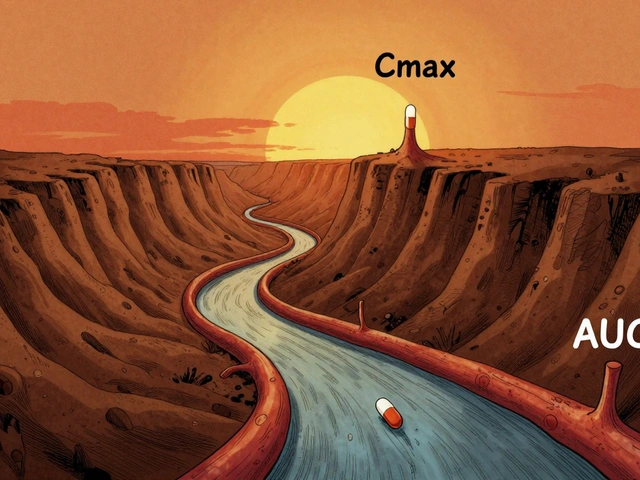

Medications don’t magically appear in breast milk. They travel through your body like everything else-through your blood. From there, they pass into the milk-producing cells in your breasts, mostly by passive diffusion. Think of it like water seeping through a sponge: the drug moves from where it’s more concentrated (your blood) to where it’s less concentrated (your milk). Not all drugs make the trip equally. Four key things determine how much gets through:- Molecular weight: Drugs under 200 daltons slip through easily. Larger molecules, like heparin or insulin, barely get in.

- Lipid solubility: Fats love drugs. The more a drug dissolves in fat, the more likely it is to enter milk. That’s why some antidepressants and anti-anxiety meds show up in higher amounts.

- Protein binding: If a drug is tightly glued to proteins in your blood (over 90%), it can’t float freely into milk. Warfarin and many NSAIDs are like this-very little gets through.

- Half-life: The longer a drug stays in your system, the more it can build up in milk. A drug with a 2-hour half-life clears quickly. One with a 24-hour half-life? That’s a different story.

There’s also something called ion trapping. Your blood is slightly more alkaline (pH 7.4) than breast milk (pH 7.2). Weakly basic drugs-like lithium, certain antidepressants, or barbiturates-get pulled into the milk and stuck there. This can make milk concentrations two to ten times higher than in your blood.

Right after birth, your body makes colostrum. The gaps between the cells in your breasts are wider, so more drugs can slip through. But here’s the good news: you’re only making about 30-60 mL a day in those first few days. By the time you’re producing mature milk (500-800 mL daily), those gaps have closed. So even if a drug passes through easily early on, the total amount your baby gets is still tiny.

The L1 to L5 Risk System-What Doctors Actually Use

Dr. Thomas Hale, a pioneer in breastfeeding pharmacology, created the most trusted system for classifying medications during lactation. It’s simple: five categories, from safest to most dangerous.- L1: Safest - No documented risk. Examples: acetaminophen, ibuprofen, most penicillins.

- L2: Safer - Limited data, but no negative reports in many babies. Examples: sertraline, fluoxetine, amoxicillin.

- L3: Moderately Safe - Either limited data or mild side effects reported. Use if benefit outweighs risk. Examples: citalopram, azithromycin, metformin.

- L4: Possibly Hazardous - Evidence of risk, but maybe acceptable in life-threatening situations. Examples: lithium, cyclosporine, some anticonvulsants.

- L5: Contraindicated - Proven risk. Avoid completely. Examples: radioactive iodine, chemotherapy drugs, bromocriptine.

This system isn’t perfect, but it’s the best tool we have. And it’s not about whether a drug is in milk-it’s about whether it’s harmful in milk. For example, lithium is in L4 because it can build up in a baby’s system and cause toxicity. But sertraline? Even though it shows up in milk, babies rarely have any side effects. That’s why L2 drugs are often the go-to for depression during breastfeeding.

Common Medications and What the Data Shows

Most women take meds while breastfeeding. Studies show over half do. Here’s what’s most common-and what we know about safety.- Analgesics (28.7%): Acetaminophen and ibuprofen are L1. Both are safe, with minimal transfer. Avoid aspirin in large doses-it can cause Reye’s syndrome in infants.

- Antibiotics (22.3%): Penicillins, cephalosporins, and macrolides like azithromycin are L1 or L2. Even metronidazole, once thought risky, is now considered safe at standard doses. Only tetracycline (L3) needs caution due to tooth discoloration risk.

- Psychotropics (15.6%): Sertraline is the top choice for depression-it’s L2, has low transfer, and studies show no developmental issues. Fluoxetine is L2 but has a long half-life, so it can build up. Paroxetine is also low-risk. Avoid benzodiazepines like diazepam (L3) if possible-they can cause drowsiness in newborns.

- Thyroid meds: Levothyroxine is L1. It’s safe and necessary if you have hypothyroidism.

- Birth control: Progestin-only pills (mini-pill) are safe. Estrogen-containing pills can reduce milk supply-avoid them in the first few months.

One big myth: “If it’s safe for babies, it’s safe for breastfeeding.” That’s mostly true. If a drug is approved for infants, it’s usually fine in milk. But not always. For example, codeine is safe for babies over 1 year, but in breastfeeding, it can turn into morphine in your body and overdose your baby. That’s why codeine is now L4 and discouraged.

When and How to Take Medications to Minimize Risk

Timing matters more than you think. You don’t have to stop breastfeeding. You just need to time it right.- Take your dose right after feeding. That gives your body time to clear the drug before the next feed.

- If you take a drug once a day, take it after your baby’s longest sleep stretch-usually at night.

- For drugs taken multiple times a day, take them just before a feed. This lets the drug peak and start clearing before the next feeding.

- Avoid extended-release versions unless necessary. They keep drug levels high longer.

- For topical meds (creams, patches), avoid applying them to the breast or nipple. If you do, wash it off before feeding.

There’s no need to “pump and dump.” Unless you’re on chemotherapy or radioactive iodine, dumping milk doesn’t help. The drug clears from your blood naturally. Pumping just makes your body produce more milk-and more drug transfer.

Where to Get Reliable Info-And What to Avoid

Not all sources are created equal. Here’s what works:- LactMed (NIH): Free, updated daily, covers over 4,000 drugs and 350 herbal products. Used by over a million people a year. The downside? It’s technical. Great for doctors, confusing for moms.

- Hale’s Medications and Mothers’ Milk (2022): The go-to for clinicians. Uses the L1-L5 system. Clear, practical, and focused on what you can actually do.

- MotherToBaby (OTIS): Free phone and chat service. Staffed by specialists. Handles 15,000 calls a year. Perfect for quick, personalized advice.

- InfantRisk Center: Offers a free app with real-time data and even research from their MilkLab study-measuring actual drug levels in milk from real moms.

Avoid Google searches, Reddit threads, or well-meaning but untrained friends. One 2021 survey found that 78% of lactation consultants see at least one case a month where a mom was told to stop breastfeeding over a medication that was actually safe.

What About Newer Drugs? Biologics, Cancer Meds, and What’s Coming

Most data comes from older, generic drugs. Newer ones? Not so much.Of the 85 FDA-approved biologic drugs (like Humira, Enbrel), only 12 have enough data to say they’re safe in breastfeeding. That’s a gap. But progress is coming. In 2022, the FDA urged drug companies to include breastfeeding women in trials. That should improve data over the next 5-7 years.

For cancer drugs, most are still L5. But some targeted therapies are showing promise. One 2023 study found that a few oral cancer drugs had very low transfer rates. More research is needed, but the future is looking less scary.

By 2030, experts predict we’ll be using personalized lactation pharmacology. That means testing a mom’s genes to predict exactly how much of a drug will end up in her milk. Accuracy could hit 85-90%. That’s not science fiction-it’s the next step.

Bottom Line: You Can Breastfeed While Taking Meds

Fewer than 1% of medications require you to stop breastfeeding. Less than 2% of babies have any serious side effects from drug exposure through milk.Don’t let fear silence your health. If you need a medication, talk to your doctor. Use LactMed or call MotherToBaby. Don’t guess. Don’t quit breastfeeding unless a professional tells you to.

Medications aren’t the enemy. Ignorance is. With the right info, you can take care of yourself-and keep giving your baby the best start possible.

Karen Conlin

Just want to say this is the most practical, no-BS guide I’ve ever read on meds and breastfeeding. I was terrified to take my antidepressant after my daughter was born-until I found LactMed. Sertraline saved my sanity and my milk supply. You’re not weak for needing help. You’re a hero for staying on it.

And no, you don’t have to pump and dump. That’s a myth pushed by people who’ve never actually nursed a 3 a.m. baby while sobbing into a burp cloth.

asa MNG

lol so like… if i take adderall is my baby gonna turn into a little zombi?? 😵💫 i just need to stay awake to change diapers and also not cry over spilled oatmeal 🤡我妈说吃药就别母乳了… but idk man i need to function

Sushrita Chakraborty

While the information presented here is largely accurate and well-referenced, I would like to respectfully suggest that the L1–L5 classification system, though widely adopted, is not universally standardized across all medical jurisdictions. In India, for instance, the National Medicines Policy emphasizes individualized risk-benefit analysis over categorical labeling, particularly for psychotropic agents. The data on sertraline remains robust, but regional variations in infant metabolism and cultural perceptions of medication use must be considered in clinical counseling.

Josh McEvoy

so wait… so i can take my weed gummies?? 🤔 i mean, i only smoke like… twice a week? and my baby is 6 months? i just want to chill without feeling like a monster. also can i still hug my kid after? 😅

Heather McCubbin

They say 99% of meds are safe but what about the 1% that ruins your baby’s brain? You think you’re being responsible but you’re just gambling with a human life. I know a mom who took Zoloft and her kid didn’t speak until 5. Coincidence? Maybe. But I’m not taking chances. I pumped and dumped for 6 months. My baby’s fine. Your choice.

Also, why do doctors always push meds? They don’t have to sleep with a screaming baby at 3 a.m.

Tiffany Wagner

I took amoxicillin for a sinus infection when my son was 2 weeks old. Didn’t even think twice. He was fine. Honestly, the hardest part was just remembering to take the pill between feedings. My milk supply didn’t drop. My anxiety did. This post helped me feel less alone.

Helen Leite

THEY’RE HIDING THE TRUTH. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know that EVERY SINGLE DRUG IN YOUR MEDICINE CABINET IS DESIGNED TO MAKE YOU DEPENDENT. LactMed? That’s a front. The FDA is owned by Pfizer. Your baby’s brain is being altered by ibuprofen. They told you it was safe… but they lied. I saw a video. A baby had a seizure after his mom took Tylenol. They covered it up. I’m not nursing anymore. I’m not letting them poison my child.

Also, the moon is made of cheese. Ask the chemists.

Elizabeth Cannon

My OB told me to stop breastfeeding because I took a single dose of ibuprofen. I cried for an hour. Then I found LactMed. Turns out, I was fine. But why do doctors still scare women like this? I had to Google it myself because no one gave me real info. We need better education. Not fear. Just facts. And maybe a hug.

siva lingam

Wow. 15 paragraphs on how to not die from a pill. The real question is why are we even talking about this? Just give the baby formula. It’s cheaper, easier, and your milk doesn’t magically become a pharmacy. Also, why is everyone so obsessed with breastfeeding? It’s not a virtue. It’s biology.

Shelby Marcel

so what about melatonin?? i’ve been taking 3mg to sleep and my 4mo is suddenly sleeping 6 hours straight… is that a coincidence or is he basically on a sleep aid??

blackbelt security

This is the kind of info that should be handed out at every hospital. No fluff. No fear. Just science. I’m a dad, but I read this so I could support my wife better. She’s been taking metformin for PCOS and I was worried. Now I know she’s doing the right thing. Thank you.

Patrick Gornik

Let’s deconstruct the epistemological fallacy embedded in the L1–L5 paradigm: it assumes a linear, reductionist model of pharmacokinetics that ignores the emergent complexity of lactational biochemistry, infant hepatic maturation, and the ontological paradox of maternal identity as both vessel and agent. The system is a relic of 20th-century pharmaceutical hegemony, designed to sanitize risk under the illusion of clinical objectivity. Meanwhile, the real issue isn’t drug transfer-it’s the cultural coercion to breastfeed at all costs, turning maternal physiology into a moral battlefield.

And yes, I’ve read Hale. Twice. With footnotes.

Tommy Sandri

The data presented here is methodologically sound and aligns with current international guidelines on lactational pharmacotherapy. The integration of LactMed and MotherToBaby as primary resources is commendable. For healthcare professionals, this represents a valuable framework for patient counseling. I would recommend this resource be disseminated through obstetric and pediatric training curricula globally.

Shanta Blank

THEY KNOW. They know we’re scared. That’s why they made this post. To make us feel safe. But what if the real danger isn’t the drug? What if it’s the silence? The way no one talks about the rage you feel when your baby cries and you’re too tired to cry back? What if the meds are the only thing keeping you from snapping? And they tell you it’s fine… but they don’t tell you how much of you is in that milk. How much of your soul is leaking out with every drop.

I took sertraline. My baby’s fine. But I’m not. And no one asks.

Jenna Allison

Quick tip: if you’re on a new med, check the half-life. If it’s under 4 hours, you’re golden. Take it right after a feed. Wait 4 hours. Feed again. Done. I did this with azithromycin and my 8-week-old had zero issues. Also, don’t panic if your baby’s poop turns green. That’s just the antibiotics doing their thing. Not poison. Just… nature being weird.