Acute Skeletal Muscle Condition Identifier

Identified Condition:

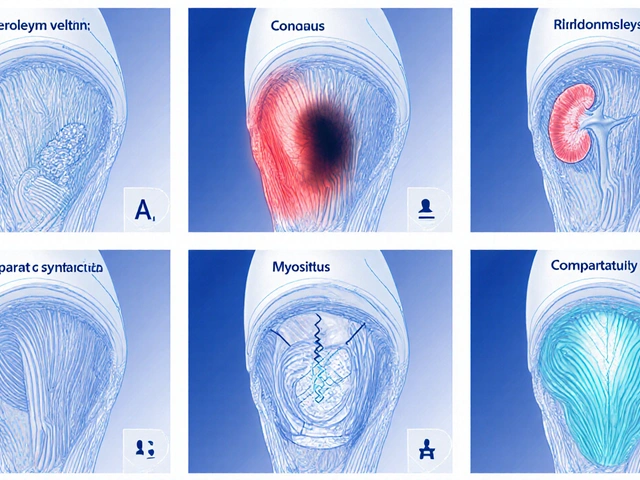

Common Acute Skeletal Muscle Conditions

Muscle Strain

Overstretched muscle fibers, graded I-III. Usually heals with rest and rehabilitation.

Muscle Contusion

Bruising from direct impact. May lead to compartment syndrome if severe.

Muscle Tear

Torn muscle fibers. Complete tears often require surgery for full recovery.

Rhabdomyolysis

Severe muscle breakdown. Can cause kidney damage. Requires urgent medical care.

Compartment Syndrome

Increased pressure in muscle compartments. Medical emergency requiring fasciotomy.

Myositis

Inflammation of muscle tissue. May be caused by trauma or infection.

When doctors talk about Acute Skeletal Muscle Conditions is a group of sudden‑onset problems that affect the muscles attached to the skeleton, causing pain, weakness, or loss of function. These conditions range from mild strains to life‑threatening rhabdomyolysis, and each needs a tailored approach for diagnosis and care.

- Know the five most common acute muscle conditions and how they differ.

- Spot the red‑flag symptoms that demand urgent medical attention.

- Learn quick first‑aid steps you can apply at home.

- Understand which imaging or lab tests confirm each diagnosis.

- Get a clear treatment roadmap from rest to rehab.

Why a Separate guide for acute muscle problems?

Muscle injuries are easy to overlook because they often feel like a simple sore. But an acute muscle condition can progress fast, especially when swelling compresses nerves or when breakdown products flood the bloodstream. Knowing the exact type helps you avoid complications such as chronic pain, permanent loss of strength, or kidney damage.

Core entities you’ll encounter

Throughout this guide we’ll refer to the following key concepts, each linked to a specific attribute set:

- Muscle Strain - overstretched fibers, graded I‑III.

- Muscle Contusion - direct blow causing bruising.

- Partial/Complete Muscle Tear - torn bundles, often surgical.

- Rhabdomyolysis - massive muscle breakdown, high CK levels.

- Compartment Syndrome - pressure buildup, risk of tissue death.

- Myositis - inflammatory muscle disease, can be traumatic.

- MRI - imaging gold‑standard for soft‑tissue detail.

- CK Levels - blood test indicating muscle cell leakage.

Type‑by‑type breakdown

1. Muscle Strain (Pulled Muscle)

A strain occurs when muscle fibers stretch beyond their limit. Grades:

- Grade I: Microscopic tears, mild soreness, <24‑hour recovery.

- Grade II: Partial tear, noticeable swelling, 2‑6 weeks rehab.

- Grade III: Complete rupture, loss of function, often surgery.

Typical signs: sudden snap or pop, localized tenderness, bruising. Diagnosis often starts with a Physical Examination and may be confirmed by MRI for Grade II‑III injuries.

Initial care follows the PRICE protocol (Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) for the first 48‑72hours, followed by gentle stretching and progressive loading.

2. Muscle Contusion (Bruise)

A direct impact crushes muscle fibers and blood vessels, causing a hematoma. Common in contact sports or traffic accidents.

Key symptoms: swelling, deep bruise color change, painful movement, possible “muscle wheel” feeling when tapping the area.

Ultrasound can quickly assess fluid collection, while MRI is reserved for large hematomas threatening neurovascular structures.

Management includes cooling, compression, and monitoring for compartment pressure. If swelling exceeds 30mmHg for >2hours, surgical fasciotomy may be needed.

3. Partial or Complete Muscle Tear

When the strain progresses to a visible gap in the muscle, you have a tear. Partial tears behave like high‑grade strains; complete tears involve a full‑thickness gap.

Symptoms: visible defect, severe pain, inability to contract the affected muscle, palpable gap.

Imaging choice: MRI provides exact location and retraction length, guiding surgical decisions.

Non‑operative tears heal with immobilization (2‑3weeks) then graded rehab. Complete ruptures of major muscles (e.g., quadriceps) often need operative repair within 2weeks to restore strength.

4. Rhabdomyolysis

This is the most dangerous acute muscle condition. Massive muscle cell death releases myoglobin, potassium, and creatine kinase (CK) into the bloodstream, potentially causing acute kidney injury.

Triggers include crushing injuries, extreme exercise, prolonged immobilization, or certain drugs. Typical CK values exceed 5,000U/L (often >20,000U/L).

Red‑flag signs: dark‑colored urine, swelling, generalized weakness, and electrolyte disturbances (high K⁺, low Ca²⁺).

Immediate treatment: aggressive IV fluid resuscitation (≈1L/h) to flush myoglobin, correct electrolytes, and monitor renal function. Dialysis is reserved for refractory cases.

5. Compartment Syndrome

Elevated pressure within a closed fascial compartment compromises blood flow, leading to ischemia and necrosis. It can follow fractures, severe contusions, or reperfusion injuries.Classic “5P’s”: Pain out of proportion, Paresthesia, Pallor, Pulselessness (late), Paralysis (late).

Diagnosis: compartment pressure measurement >30mmHg or within 30mmHg of diastolic BP. Immediate fasciotomy saves tissue.

Even if pain subsides after analgesics, never dismiss the possibility; timing is critical.

6. Myositis (Inflammatory)

Acute traumatic myositis is inflammation of muscle fibers triggered by injury or infection. It presents with diffuse pain, swelling, and low‑grade fever.

Labs show modest CK rise (500‑1,500U/L) and elevated ESR/CRP. MRI reveals hyper‑intense signal on T2‑weighted images.

Management includes NSAIDs, occasional short‑course steroids, and physiotherapy once pain eases.

Comparison of Key Acute Muscle Conditions

| Condition | Main Trigger | Critical Red‑Flag | First‑Line Test | Treatment Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle Strain (Grade I‑III) | Over‑stretch or sudden load | Complete loss of function (Grade III) | Physical exam, optional MRI | Rest → Rehab (surgery if Grade III) |

| Muscle Contusion | Direct blunt trauma | Progressive swelling → compartment risk | Ultrasound, MRI if large | Ice/compression → monitor pressure |

| Muscle Tear (Partial/Complete) | Severe overload or laceration | Visible gap, inability to contract | MRI (gold standard) | Immobilize → surgical repair if complete |

| Rhabdomyolysis | Crush, extreme exercise, toxins | Dark urine, CK >5,000U/L | Serum CK, electrolytes, renal labs | IV fluids urgently → dialysis if needed |

| Compartment Syndrome | Trauma, reperfusion, tight cast | Pain > 30mmHg pressure | Compartment pressure probe | Emergency fasciotomy |

| Myositis (Traumatic) | Localized infection or severe strain | Fever + rapidly rising CK | MRI + inflammatory markers | NSAIDs ± steroids → rehab |

Step‑by‑step: What to do when you suspect an acute muscle condition

- Assess pain and function. Can the muscle contract? Is pain worsening with passive stretch?

- Apply immediate care. Use ice (15min, every 2h) and compress the area. Keep the limb elevated if possible.

- Seek professional evaluation. If you notice severe swelling, loss of pulse, dark urine, or inability to move, go to an urgent‑care or emergency department.

- Diagnostic work‑up. Expect a physical exam, possibly an ultrasound, MRI, and blood tests like CK and electrolytes.

- Follow the treatment plan. Rest, gradual loading, medication, or surgery as directed. Adhere to physiotherapy milestones to avoid re‑injury.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Ignoring pain. Pushing through severe pain often converts a Grade I strain into a Grade II‑III tear.

- Using heat too early. Heat increases blood flow and swelling; reserve it for the sub‑acute phase (48‑72h after injury).

- Skipping follow‑up imaging. A normal X‑ray does not rule out soft‑tissue damage; MRI is essential for high‑grade tears.

- Under‑hydrating after crush injuries. Low fluid intake raises the risk of rhabdomyolysis‑related kidney injury.

- Failing to monitor compartment pressure. Late recognition can lead to permanent muscle loss.

When to call emergency services

If any of the following appear, dial emergency services immediately:

- Severe, unrelenting pain with a feeling of tightness (possible compartment syndrome).

- Dark brown or tea‑colored urine (sign of myoglobin).

- Rapid swelling that distorts limb shape.

- Visible muscle protrusion or empty‑felt gap.

- Signs of systemic toxicity: fever, confusion, irregular heartbeat.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does a Grade II muscle strain usually take to heal?

Most GradeII strains improve within 3‑4weeks of proper rest, ice, compression and a supervised physiotherapy program. Return to full sport usually occurs after the muscle regains at least 90% of its pre‑injury strength.

Can I treat a muscle contusion at home?

Mild contusions often respond to the RICE method (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) for 48‑72hours. Monitor for increasing pain, numbness, or swelling; if those develop, seek medical evaluation for possible compartment syndrome.

What CK level indicates rhabdomyolysis?

A CK level above 5,000U/L is generally accepted as rhabdomyolysis, though values can soar past 20,000U/L in severe cases. The trend and accompanying symptoms guide urgency.

Is surgery always required for a complete muscle tear?

Not always, but for major muscles (e.g., quadriceps, biceps) a surgical repair within 2weeks offers the best chance to restore full strength and prevent chronic weakness. Small peripheral tears may be managed conservatively.

How can I prevent compartment syndrome after a leg injury?

Early elevation, avoiding tight casts or bandages, and monitoring pain that is out of proportion to the injury are key. If swelling appears rapid, have a clinician measure compartment pressures.

Anthony Aspeitia-Orozco

When you look at acute skeletal muscle conditions, it helps to think of the muscle as a bridge between the brain's intentions and the body's actions. A strain, a contusion, or a tear is not just a flash of pain; it’s a signal that the bridge is under stress. The severity grade tells you how much of the bridge is compromised, and that guides how you reinforce it. Early rest and ice are like temporary supports that prevent the bridge from collapsing under load. As the inflammation settles, gentle motion re‑establishes the connections that were lost. Skipping the rehabilitation phase is like removing the planks before the bridge is fully repaired – you’ll end up with a wobble that can cause chronic instability. Rhabdomyolysis, on the other hand, is a flood that can wash away the foundation of the bridge if you don’t pump enough fluids to clear the debris. Monitoring CK levels is akin to testing the water quality; rising numbers warn you that the flood is getting worse. Compartment syndrome is the pressure that builds when debris gets trapped in a confined space, and only a fasciotomy can open a new passage for relief. Imaging, especially MRI, gives you a blueprint of the damage, showing you exactly where the bridge has cracks. Blood tests tell you whether the flood has contaminated the kidneys, which are the filtration plant of the whole system. The key is to match the urgency of the condition with the urgency of the intervention – a Grade I strain can heal with a few weeks of RICE, while a complete muscle tear often needs surgery within days. Rehabilitation isn’t just about getting strong again; it’s about restoring proprioception so the brain can trust the bridge again. Nutrition, hydration, and sleep are the quiet workers that lay down new concrete beneath the visible repairs. Remember, the goal isn’t just to return to the status quo, but to build a stronger, more resilient bridge that can handle future stresses without failing. In practice, this means a phased return to activity, starting with low‑impact movements and progressing only when pain‑free range of motion and strength are restored. Finally, keep an eye on red‑flag symptoms – dark urine, uncontrolled swelling, or a sudden loss of pulse – because they indicate that the bridge is under imminent danger and you need emergency help. By respecting these principles, you turn a painful setback into an opportunity for smarter, safer performance.

Adam Dicker

Whoa, this guide packs a punch! I love how it pulls no punches about rhabdo and compartment syndrome – those are the real game‑changers. The step‑by‑step checklist is pure gold for anyone who’s ever twisted a calf or taken a hard hit. Remember, the moment you see a "tight like a drum" feeling, act fast. No bragging, just getting the pressure off before it kills the muscle. And that table? Visual proof that you can’t ignore the numbers – CK over 5k screams danger. Keep the ice, stay hydrated, and don’t be a hero – you’re not invincible.

Molly Beardall

Okay i gotta say this article is super helpful but also a bit overwhelming lol. The part about "dark brown urine" made me shiver bc i once thought it was just my coffee lol. Also, the phrase "RICE method" i always forget what it stands for – rest, ice, compression, elevate – easy peasy. One thing i wish was added is how to spot a hidden tear after a gym sesh – sometimes you just feel a weird pop and think it’s fine. Overall great info, please keep adding more real life examples!!

Brian Pellot

Great rundown! It’s impressive how the guide breaks down each condition without drowning you in jargon. I appreciate the emphasis on “early red‑flags” – catching compartment syndrome early can save a limb. The RICE steps are spot‑on for most strains, and the reminder to avoid heat too soon is a nice touch. For anyone in the gym, remember to listen to your body and don’t push through sharp pain. A solid rehab plan beats a rushed comeback any day.

Patrick McCarthy

Interesting guide. Which imaging is best for a partial tear probably MRI. Also CK levels important for rhabdo but how often should they be checked after a crush injury definitely every few hours initially. The table format makes it easy to compare. I wonder if there are any dietary tips to aid recovery especially for severe muscle damage.

Geraldine Grunberg

Wow, what a comprehensive guide, and thank you for including such clear tables, detailed descriptions, and actionable steps! I especially love the way you highlighted the emergency signs-dark urine, uncontrolled swelling, and severe pain-because those are the critical cues that can’t be ignored. The emphasis on early imaging, especially MRI for high‑grade tears, is spot‑on; it really helps clinicians plan the right intervention. Also, the step‑by‑step first‑aid list is perfect for anyone who might be the first responder in a sports setting. Great job making this both thorough and readable, and please keep the updates coming!

Elijah Mbachu

Totally agree with the earlier point about gradual rehab. After a Grade II strain, I found that starting with low‑impact activities like swimming helped restore range of motion without overloading the muscle. Consistency is key; a few minutes each day beats a marathon session once a week. Also, keeping a simple log of pain levels can guide when to progress. Small steps lead to big gains.

Sunil Rawat

Hey, great stuff! From my experience in cricket, we often see contusions after a hard ball impact. I always make sure to elevate the leg and apply ice, but I also pay attention to any signs of swelling that could turn into compartment syndrome. In our region, staying hydrated is a big part of preventing rhabdo, especially in hot weather. Thanks for the clear reminders!

Andrew Buchanan

The guide’s breakdown of diagnostic tests is very precise. I’d add that an ultrasound can be a quick first step for superficial tears before ordering an MRI. Also, checking peripheral pulses is essential when suspecting compartment syndrome. Overall, a solid reference for clinicians and athletes alike.

Krishna Chaitanya

Wow!!! This really hit home. When I got a nasty hamstring pull, I ignored the pain and it turned into a full tear – total nightmare! The part about “don’t use heat too early” is a lifesaver, because I was heating it and it just got worse. Thanks for shouting out the red flags – I’ll definitely keep this on my phone for next time.

diana tutaan

This article overstates the prevalence of some conditions and underplays the role of proper conditioning. Not every muscle pain is a red‑flag; many are just delayed‑onset soreness that resolves with rest. The guide could benefit from a more balanced view that distinguishes everyday aches from true emergencies.

Sarah Posh

Excellent point, it really helps to stay realistic.