Thiazolidinediones Help Control Blood Sugar - But at a Cost

Thiazolidinediones, or TZDs, are oral diabetes drugs that make your body more sensitive to insulin. That sounds great - better insulin response means lower blood sugar without the risk of dangerous lows. Two names you might recognize: pioglitazone (Actos) and rosiglitazone (Avandia). They’ve been around since the late 1990s. But here’s the catch: for every person who benefits, another might end up with swollen ankles, shortness of breath, or worse - heart failure.

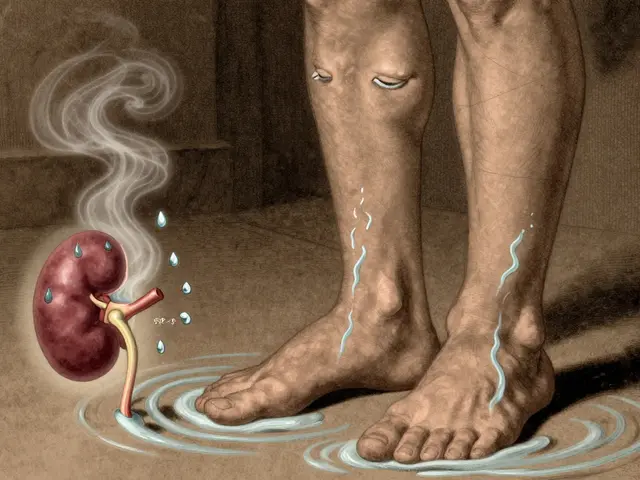

How TZDs Cause Fluid Retention - And Why It Matters

These drugs don’t just work in muscle and fat cells to improve insulin sensitivity. They also turn on receptors in your kidneys. That’s where the trouble starts. When PPAR-γ receptors in the kidney tubules get activated, your body starts holding onto more sodium and water. It’s not a small amount. Studies show TZDs can increase blood volume by 6-7%. That extra fluid doesn’t just sit around - it leaks into tissues, causing swelling in the legs and feet. About 7% of people on TZDs alone get noticeable edema. That number jumps to 15% if they’re also taking insulin.

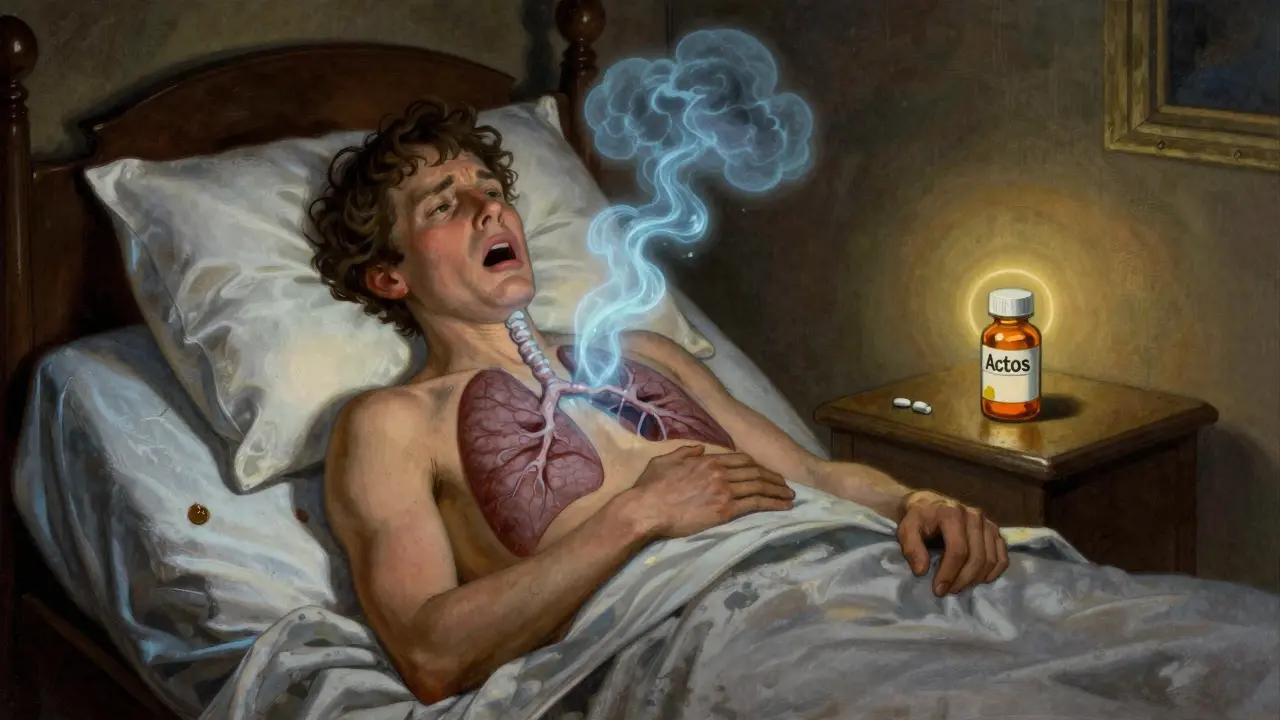

And it’s not just cosmetic. That fluid can move into the lungs. Pulmonary edema isn’t rare in TZD users with existing heart problems. One study followed 111 diabetic patients with heart failure and found that 17% gained over 10 pounds and developed swelling. Two of them ended up with fluid in their lungs. Women and people on insulin were at higher risk - even if their heart failure wasn’t severe.

Why Loop Diuretics Often Don’t Work

If you’ve ever had swelling from heart failure, your doctor probably reached for a diuretic like furosemide. But TZD-induced fluid retention doesn’t always respond the way you’d expect. Unlike typical heart failure fluid buildup, this one is stubborn. Loop diuretics - the go-to treatment - often fail to flush out the extra volume. Why? Because the problem isn’t just the heart pumping poorly. It’s the kidneys being told by the drug to hold on to salt and water. Until you stop the TZD, the body keeps reabsorbing what you try to pee out.

The good news? Once you stop the drug, the fluid usually goes away. Within days to weeks, swelling fades, weight drops, and breathing improves. But that’s only if you catch it early.

Who Should Never Take TZDs

The FDA’s black box warning is clear: don’t use TZDs if you have Class III or IV heart failure. That means you’re uncomfortable at rest, or you can’t do any physical activity without severe symptoms. But here’s what’s scary - many people who are prescribed TZDs already have heart failure, even if they don’t know it.

A 2018 analysis of over 424,000 diabetic patients found that 40.3% of TZD users had signs of heart failure: either a diagnosis, reduced heart pumping ability (ejection fraction under 40%), or were already on loop diuretics. That’s more than two in five people taking these drugs who shouldn’t be. Many doctors still prescribe them because the patient feels fine - no swelling, no shortness of breath. But the risk is hiding under the surface.

Who Might Still Be a Candidate - With Caution

Not everyone with heart failure is automatically off-limits. If you have mild heart failure - Class I or II - and your symptoms are stable, some guidelines say TZDs can be used, but only with tight monitoring. That means weekly weight checks, watching for swelling, and listening to your body. If you gain more than 2-3 pounds in a week, it’s a red flag. So is new shortness of breath when walking to the mailbox.

Experts agree: TZDs aren’t first-line anymore. But for some people - especially those with severe insulin resistance, obesity, or who can’t tolerate other drugs - they’re still useful. The key is knowing your limits. If you have coronary disease, kidney issues, or are over 65, you’re already in a higher-risk group. That doesn’t mean you’re automatically excluded, but it means your doctor needs to be extra careful.

What the Guidelines Say Today

The American Diabetes Association’s 2022 guidelines say: avoid TZDs in patients with heart failure. If you have it, use them only if no other options exist - and only if your condition is stable. The American Heart Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists are even stricter. They recommend avoiding TZDs entirely in anyone with heart failure or at high risk.

And here’s the reality: even though safety warnings have been out since 2007, and rosiglitazone’s heart attack risk sparked major restrictions, TZDs are still prescribed. About 8.3% of diabetic patients on glucose-lowering meds are still on them. Most are older adults - average age nearly 70 - with a history of heart disease and obesity. That’s not a coincidence.

What to Do If You’re on a TZD

- Check your weight every morning, same time, same scale. A gain of 3 pounds or more in 2-3 days? Call your doctor.

- Watch for swelling in ankles, feet, or belly. Press on your shin - if it leaves a dent, that’s edema.

- Pay attention to breathing. Does climbing one flight of stairs leave you winded? That’s new.

- Don’t assume your diuretic is doing its job. If you’re on furosemide and still swelling, the problem might be the TZD.

- Ask: Is there a safer alternative? Metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors, or GLP-1 agonists are now preferred for most people.

The Bigger Picture: Benefits vs. Risks

TZDs aren’t useless. They lower blood sugar effectively, don’t cause hypoglycemia, and may even help reduce artery-clogging plaque. But those benefits don’t outweigh the risks for most people anymore. Newer drugs like empagliflozin and semaglutide don’t just control sugar - they protect the heart. And they don’t cause fluid retention.

That’s why TZDs have faded from first-choice status. They’re not banned. They’re not gone. But they’re becoming relics - useful in very narrow cases, and dangerous in too many others.

Final Thought: Your Body Is Telling You Something

Swelling isn’t just a side effect. It’s a warning. If you’re on a TZD and your socks leave marks on your legs, or you’re waking up with puffy eyes, don’t brush it off. That’s your body saying: "This drug is making me hold too much fluid." And if your heart is already weak, that’s not a small thing.

It’s okay to ask your doctor: "Is this still the right drug for me?" The answer might be yes - but only if you’re being watched closely. Otherwise, it’s time to move on to something safer.

Can thiazolidinediones cause heart failure in people who don’t have it?

Yes, in susceptible individuals - especially those with kidney problems, older adults, or those on insulin - TZDs can trigger fluid overload that leads to heart failure symptoms, even if they didn’t have heart disease before. It’s not common, but it happens often enough that guidelines warn against using these drugs in anyone with risk factors.

Are all thiazolidinediones equally risky for fluid retention?

Yes. Both pioglitazone (Actos) and rosiglitazone (Avandia) cause fluid retention at similar rates - about 5% as monotherapy and up to 15% with insulin. The mechanism is the same. Neither is safer than the other when it comes to swelling or heart failure risk.

Why aren’t TZDs banned if they cause heart failure?

They’re not banned because they still work well for blood sugar control in certain patients - especially those with severe insulin resistance who can’t use other drugs. The FDA requires black box warnings and restricts use, but doesn’t remove them from the market because the benefits can outweigh risks in rare, carefully selected cases.

What are the signs that TZD-induced fluid retention is getting serious?

Weight gain over 3-5 pounds in a few days, swelling that spreads to your belly or lower back, new shortness of breath when resting, needing more pillows to sleep, or waking up gasping for air. These aren’t normal side effects - they’re red flags for pulmonary edema or worsening heart failure.

How long does it take for fluid retention to go away after stopping a TZD?

Most people see improvement within a week. Swelling fades, weight drops, and breathing gets easier. Full recovery usually takes 2-4 weeks. But if you’ve had prolonged fluid overload or heart strain, it may take longer - and you’ll need follow-up with your doctor to make sure your heart is recovering properly.

Is pioglitazone (Actos) safer than rosiglitazone (Avandia) for the heart?

In terms of fluid retention and heart failure risk, no. Both drugs carry the same warnings. Rosiglitazone had additional concerns about heart attacks, which led to restrictions, but both cause fluid retention equally. Pioglitazone is still available because it doesn’t carry the same heart attack risk signal - but that doesn’t make it safer for people with heart failure.

Kipper Pickens

From a clinical pharmacology standpoint, TZDs activate PPAR-γ in the collecting ducts of the nephron, upregulating ENaC channels and increasing sodium reabsorption - that’s the mechanistic root of the volume expansion. The fluid retention isn’t cardiogenic per se; it’s nephrogenic. That’s why loop diuretics often underperform - they’re targeting the wrong node in the pathway. You need to hit the receptor, not the symptom.

Allie Lehto

i was on actos for 2 years and never knew my ankles were puffier than a marshmallow until my mom said "honey u look like you swallowed a balloon" lmao. then i gained 8lbs in 10 days and my dr pulled me off it. poof. gone. like magic. why do docs keep prescribing this stuff??

Henry Jenkins

I’ve seen this play out in my clinic too - patients come in with "just a little swelling" and it’s already stage 2 heart failure hiding in plain sight. The scary part isn’t the obvious cases. It’s the 68-year-old with a 35% EF who’s asymptomatic, on insulin, and on pioglitazone because "it’s the only thing that keeps his HbA1c under 7." They’re walking time bombs. We need better screening protocols - not just relying on patient self-report. Echocardiograms should be routine before prescribing TZDs to anyone over 60 with metabolic syndrome.

And honestly? The fact that 8.3% of diabetics are still on these is a systemic failure. Pharma pushed these hard, guidelines changed, but the prescribing inertia? Unbelievable.

Conor Flannelly

It’s fascinating how medicine keeps chasing efficacy while ignoring the body’s quiet screams. TZDs are like a strict teacher who gives perfect grades but makes you cry every day. You get the numbers you want - but at what cost to your actual life? Fluid retention isn’t just a side effect. It’s your kidneys screaming, "We’re not supposed to hold this!" And yet we keep giving them more salt to hold. We treat the glucose like the enemy, not the whole person.

Maybe the real question isn’t "Is this drug safe?" but "Are we treating diabetes like a number or a human?"

I’ve had patients who stopped TZDs and said they felt like they could breathe again for the first time in years. Not because their sugar changed - because their body finally stopped fighting itself.

We’ve forgotten that medicine isn’t just about control. It’s about harmony.

And sometimes, the most powerful prescription is saying no.

Dan Nichols

People don’t realize how many of these "safe" drugs are just slow poison. TZDs are a perfect example. They work. So we ignore the edema. Then the heart fails. Then we blame the patient for not "taking care of themselves." Newsflash: if your drug makes you retain fluid like a sponge, it’s not the patient’s fault. It’s the drug’s. And if your doctor still prescribes this, fire them.

Also rosiglitazone got banned for heart attacks but pioglitazone is fine? That’s not science. That’s politics. Same mechanism. Same risk. Just less media attention.

Renia Pyles

Oh please. Another "TZDs are evil" post. Have you seen the HbA1c numbers on SGLT2 inhibitors? They’re great but they cause UTIs and ketoacidosis in people who don’t even know they’re at risk. And GLP-1s? $1000/month. Who can afford that? Not everyone lives in a rich suburb with a good insurance plan. TZDs cost $5. They work. And if you’re not in heart failure, why are you acting like it’s a death sentence?

Stop fearmongering. Not everyone is a fragile old lady. Some of us need this to survive.

Conor Murphy

My grandma was on Actos for 5 years. Never had swelling. Never had issues. She’s 82 now, walks 3 miles a day, and her sugar’s stable. I get the warnings - but blanket statements scare people away from things that might help them live better. Maybe she was lucky. Or maybe her body just handled it. Not everyone’s the same. We need nuance, not fear.

Also, my cousin’s doctor switched her to a GLP-1 and she lost 40lbs… and got pancreatitis. So now she’s back on metformin and TZD. Sometimes the "safer" option isn’t safer at all.

Nicholas Miter

Just wanted to say - if you're on a TZD and you're not sure, get a basic echo. It's cheap, non-invasive, and tells you more than any symptom ever could. I had a patient with "mild" swelling who had an EF of 32% and didn't even know it. Stopped the TZD, started on an SGLT2i, and now she's hiking. No drama. Just a quiet win.

Also - morning weights? Do it. Even if you think it's dumb. I do it. My wife makes fun of me. But I've caught two cases of early fluid overload this way. Worth it.

Suresh Kumar Govindan

It is a well-documented fact that the pharmaceutical-industrial complex has systematically suppressed data regarding the nephrotoxic potential of PPAR-γ agonists since the early 2000s. The FDA’s black box warning is a performative gesture. The real issue is that TZDs are being prescribed to populations with subclinical renal dysfunction - a condition often undiagnosed in low-resource settings. This is not medical negligence. It is structural violence.

Marian Gilan

they’re hiding something. why do all the new diabetes drugs come with heart benefits but tzds only have side effects? coincidence? i think not. the fda and big pharma are in bed together. they want you on the expensive stuff. the real reason tzds aren’t banned? they’re too cheap. they don’t make enough money. this isn’t medicine. it’s capitalism.

also - did you know the original studies were funded by takeda? think about that.

Patrick Merrell

If you're on a TZD and you're not monitoring your weight daily, you're playing Russian roulette with your heart. No excuses. No "but I feel fine." Fluid retention doesn't announce itself with a siren. It creeps in. And then it kills. Get off it. Or get serious.